Introduction

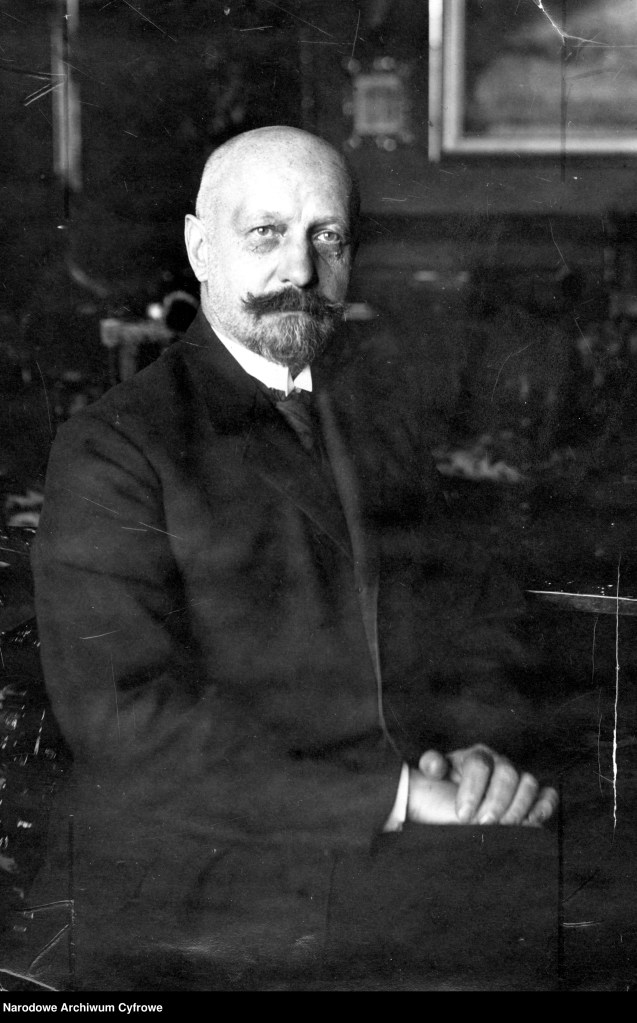

Studies of Interwar legal history seem to prove that proper comparative analysis may be an indispensable element of a sound legislative process. The history of the creation of the Polish Criminal Code of 1932 and its main drafter, Professor Juliusz Makarewicz (1872-1955), constitute such an example. Some lawyers earn a special place in the minds of their successors and enter national legal pantheons. In Poland, Makarewicz undoubtedly belongs to such a group. Every reasonably eager Polish law student will connect his name with the Criminal Code of 1932, still popularly called Lex Makarewicz. His name can be associated with the tremendous legislative challenges experienced by the reborn Polish state in the Interwar period – a topic which was explored in this series by Anna Jackowska and Krzysztof Koźmiński (who briefly referred to Makarewicz), Aleksander Grebieniow and Jan Rudnicki, and Katarzyna Kryla-Cudna However, Makarewicz’s work and intellectual activities can illustrate how international philosophical and comparative debates developed in the first half of the 20th century on their own.

Makarewicz as a Philosopher of Criminal Law

European criminal law at the turn of the 20th century was undoubtedly dominated by the sociological school, of which perhaps the most important representative was Franz von Liszt, a professor of Hungarian descent in Germany (and a relative as well as a godson of the famous romantic composer, Ferenz Liszt). Makarewicz himself came under the influence of the sociological approach to understanding crime and criminal justice. He took part in von Liszt’s seminar in 1894 (Adam Redzik, “Profesor Juliusz Makarewicz—życie i dzieło,” in Prawo karne w poglądach Profesora Juliusza Makarewicza, ed. Alicja Grześkowiak, Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL 2005, pp. 26–28). Already as a young professor, he gained international acclaim by writing a monograph entitled Einfürung in die Philosophie des Strafrechtes auf entwicklungsgeschichtlicher Grundlage (Stuttgart: Verlag von Ferdinand Enke, 1906. Title in English: “Introduction to the philosophy of criminal law on the basis of developmental history”), in which he opted for combining an historical, a comparative positivist and a natural law approach to criminal law. His monograph is still considered to be relevant today: it was reedited in Germany in 1967 and again in 1995, while a Polish translation was published in 2009. Yet, the fact that Makarewicz published his most important work in German (the lingua franca of criminal law of his time) as well as his early apprenticeship with von Liszt should not prompt a superficial classification of Makarewicz into the German sociological school. In simple terms, one can say that the sociological school favoured a deterministic perception of crime. Makarewicz, however, could not accept such an assumption because of his Catholic upbringing and faith. As an expert on the history of criminal law pointed out, Makarewicz

was inclined to believe that crime resulted from the loss of man’s ability to control his behaviour. A normal person, having an instrument of free will, can successfully avoid the temptations lurking in everyday life. A criminal is a man who has lost this instrument. There may be various reasons for this; Makarewicz lists a whole set of them, from heredity to social conditions. That is why he emphasises the role of education in human life so much. He sees upbringing as a means of strengthening human free will, making it resistant to various dangers. Man is evil by nature, Makarewicz believes, and his evil inclinations become apparent when he loses control over himself. Free will is that element of control. With this understanding of the free will/determinism relationship, the contradiction between them does lose its dramatic expression. There is no opposition here, but both principles complement each other (Marek Wąsowicz, Nurt socjologiczny w polskiej myśli prawnokarnej, Warsaw: Wydawnictwo UW, 1989, p. 91).

Codification Commission, Wacław Makowski and Politics

Therefore, as a philosopher of law, Makarewicz was not only up to date with the trends of his time, but also demonstrated considerable originality. As a professor at the Jan Kazimierz University in the then Polish city of Lwów (today’s Lviv, Ukraine, the Ivan Franko National University), he became widely recognised for his scientific achievements, his talent as a lecturer, and his internationally distinguished students (among them Hersch Lauterpacht and Rafał Lemkin, about whom Adam Krzywoń wrote a piece for this series of the BACL Blog). He was also a Christian-democratic politician and a senator of independent Poland for two consecutive terms. However, as indicated at the beginning, he is best remembered nowadays as a codifier of criminal law. Makarewicz served as a member of the Codification Commission, an authority tasked with drafting the main laws of reborn Poland, since its establishment in 1919 (For more information about the Commission, see: A. Grebieniow and J. Rudnicki in this series). The criminal law subcommittee was quickly dominated by a duo of two professors with surnames starting with the letter “M”, who outdistanced the other members with both their comprehensive expertise on the subject and their dynamic personalities. The second one was Wacław Makowski (1882-1942) from the University of Warsaw.

If a comparative study of the history of modern law codification teaches us anything, it is certainly that for the codification project to succeed at all, it must be supported not only by the intellectual work of lawyers, but also by political will. In the Second Polish Republic that political will was first embodied by the democratic parliament in the years 1919-1926 which established the above-mentioned Commission and laid strong foundations for its work, and then, after the bloody coup d’état committed by marshal Józef Piłsudski – by his authoritarian regime. Wacław Makowski, who never achieved international recognition even close to that enjoyed by Makarewicz, was – unlike his colleague from Lviv – a man closely associated with the regime. His hand is clearly visible in the text of the authoritarian Constitution of 1935 (by the way, largely copied later by the regime of President Getúlio Vargas in distant Brazil and probably exerting some influence on the political concepts of General de Gaulle, but these are certainly facets to be explored on a different occasion). Because of that, Makowski was not only one of the two dominant intellectual factors in the drafting of the criminal code (perhaps the only one who could match Makarewicz in a discussion), but also one of the links between the drafters and the highest political circles, therefore able to provide the necessary political backup.

Comparative Background of the Criminal Code of 1932

Yet Makarewicz was definitely the main intellectual engine of the subcommittee. In connection with his work on the code, he travelled to other countries, including the United States of America, Germany, Austria, and Italy, in order to familiarise himself even more with their legislation and the achievements of their criminal law scholarship. One of the conclusions of this research was the statement that certain rules, or even standards of law, have already become the common good of modern legal culture. For example, he pointed out that the principle of nullum crimen sine lege implied the possibility of being guilty and, therefore, responsible for a crime only of people of sound mind. In Makarewicz’s opinion, these standards constitute guidelines recognised by modern lawbeyond doubt (J. Makarewicz, Technika ustawodawstwa karnego, Lwów 1913, p. 11).

Comparative studies for sure helped Juliusz Makarewicz in developing proposals for the rules of a new, Polish criminal code. The experience of other countries should be wisely used, especially if the solutions adopted there have been recognised in practice. However, the criminal code is a piece of legislation of particular importance: as Makarewicz himself pointed out, it is in it that the fate of a given nation is reflected like in a mirror (T. Szczygieł, Ostatni referat Edmunda Krzymuskiego w pracach Sekcji Prawa Karnego Materialnego Komisji Kodyfikacyjnej Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej – wybrane zagadnienia, Krakowskie Studia z Historii Państwa i Prawa 2023, No 1, p. 68). In his opinion, criminal law is a precise photographic negative reflecting reality; it is therefore a photograph of the political system of the country. Consequently, the main legislation governing criminal law will always be characterised by an individualism specific to a given state, which cannot be received from foreign legislation by its very nature.

Makarewicz is recognised as an extraordinary erudite person – this is evidenced by the references to examples of criminal codes from Roman times to his contemporaries, such as the codes of Chile, Mexico, or Myanmar in his works, not to even mention the criminal codes of Germany, Austria and Russia (M. Wąsowicz, Juliusz Makarewicz – uczony i kodyfikator, Studia Iuridica 1993, No 26, p. 126). All of this broad comparative background can be easily traced in the rules of the Lex Makarewicz.

Contemporary authors point out that Makarewicz not only drew mostly from German scholarship in criminal law, but also, inspired by it, went further and developed solutions adopted earlier by the German legislator. This allowed for the adoption of what Polish legislators considered the best of the German Criminal Code of 1871, as well as for learning from its mistakes and correcting them in the new Polish rules. From that point of view, an understanding that German criminal law was borrowed by Polish legislation is generally justified. However, it should be noted that Makarewicz did not stop there. A much more complex path was chosen. First of all, German imperfections were corrected while some new ideas were developed. This creativity, together with a different perspective on certain social and cultural issues applied by the Polish legislator, can be deemed to be a certain original Polish thought in the field of criminal law. It is therefore not surprising that the Polish Criminal Code was widely discussed among German authors (Danuta Janicka, Kodeks Makarewicza w opinii niemiecki autorów).

Moreover, Polish legislators took inspiration not only from the achievements of German criminal law. Interestingly, the practice of the courts of England and the United States also had a significant impact on the Criminal Code of 1932. It was there, in the middle of the 19th century, that the idea of probationary measures was born. In Makarewicz’s opinion, it was a consequence of the unfulfilled hopes placed on the criminal-political significance of imprisonment in the 19th century. That is why, in his times, the probationary institutions were recognised and – as Makarewicz put it, using a language not alien to his times – “approved by the entire civilised world” (J. Makarewicz, Kodeks karny z komentarzem, Lwów 1932, p. 37), and they were also included in the Criminal Code of 1932. Additionally, it should be stressed that this was one of the first European pieces of legislation in which probationary elements in the form of supervision and the obligation to compensate for damage were so strongly emphasised.

In the context of the Interwar dialogue, it is also worth noting that, despite his significant inspiration from German law, Makarewicz opposed the changes introduced in it after 1933 and strongly criticised them. Moreover, he was troubled by the “innovations” of Soviet criminal law and justice system. This thread brings us close to the first, bitter, part of the conclusion of this text.

Bitter End but Lasting Legacy

The fate of both Makarewicz and Makowski, as well as many other members of the Codification Commission, is deeply symbolical. In the aftermath of the German and Soviet invasion in September 1939, Wacław Makowski (among many other members of the Polish political elite) fled to sympathetic Romania. There, in Bucharest, grievously ill and overwhelmed with trauma of the national catastrophe, he passed away three years later. Juliusz Makarewicz remained home and survived the arrest by the Soviet NKVD. In July 1941, just after entering Lviv at the beginning of Operation Barbarossa, German special police arrested and murdered more than forty of Lviv’s professors and members of their families. Kazimierz Bartel, professor of geometry and five-time prime minister of Poland, and Roman Longchamps de Bérier, Makarewicz’s colleague, professor, and codifier of civil law together with his three adult sons, were among the victims (Adam Redzik, Roman Longchamps de Bérier (1883-1941) in: Law and Christianity in Poland. The Legacy of the Great Jurists, ed. F. Longchamps de Bérier, R. Domingo, Routledge 2023, pp. 187–201). It is difficult to say why Makarewicz himself, as well as several other prominent intellectuals in Lviv, were actually spared. Dieter Schenk, criminologist and researcher of German war crimes, claims that the entire criminal operation was rushed, and the list of victims was prepared negligently (Dieter Schenk, Der Lemberger Professorenmord und der Holocaust in Ostgalizien, Bonn: J. H. Dietz, 2007, pp. 114–15). Due to lack of convincing evidence, such a simple explanation seems accurate enough.

After the war, elderly Makarewicz decided to stay in then Soviet Lviv, where he continued to give lectures (in Ukrainian), but could not express himself freely as a researcher anymore. The once famous legal philosopher and comparatist, a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, was literally cut off from international academic debate by the Iron Curtain. The position of those of the remnants of the deliberately exterminated Polish legal elite who ended up at the universities of a communist homeland was only a little bit better. They were allowed to take part again, to some extent, in the international intellectual dialogue after the political “thaw” (liberalisation of the communist regime) in 1956, but the damage was already done. However, the international and domestic legacy of Polish Interwar criminal lawyers is invaluable. For example, the Swiss Criminal Code of 1937 was modelled on the Polish Code of 1932 regarding the basis of criminal liability. In Poland, until today, the code is often seen as an important model for legislation in criminal law, especially from the perspective of legislative technique. It has also been pointed out that its merits include its modernity, its modeling on the best achievements of knowledge in the field of criminal law of that time, and the clarity and legal precision of its language.

Further reading in English: Jan Rudnicki, Juliusz Makarewicz (1872-1955) in: Law and Christianity in Poland. The Legacy of the Great Jurists, ed. F. Longchamps de Bérier, R. Domingo, Routledge 2023, pp. 175-186.

Posted by Mgr Aleksander Leszczyński (PhD candidate, University of Warsaw, aleksander.leszczynski[at]uw.edu.pl) and dr hab. Jan Rudnicki (associate professor, University of Warsaw, j.rudnicki[at]wpia.uw.edu.pl)

This piece belongs to Season 2 of the “Cross-jurisdictional dialogues in the Interwar period” series dedicated to less-known legal transfers which have had a palpable impact on the advancement of the law. The Interwar period was a time of disillusionment with well-established paradigms and legislative models, but also a time of hope in which comparative dialogue and exchange of ideas between jurisdictions thrived. The series is edited by Prof Yseult Marique (Essex University) and Dr Radosveta Vassileva (Middlesex University). To access the other pieces from this series, either select the ‘Interwar Dialogue’ category or click on the #Series_Interwar_Dialogue tag on the BACL Blog.

Suggested citation: Aleksander Leszczyński and Jan Rudnicki, ‘Lex Makarewicz (and Makowski) – the Polish Criminal Code of 1932 and Its Authors in a Comparative and Philosophical Light’, BACL Blog, available at https://british-association-comparative-law.org/2024/05/24/lex-makarewicz-and-makowski-the-polish-criminal-code-of-1932-and-its-authors-in-a-comparative-and-philosophical-light-by-aleksander-leszczynski-and-jan-rudnicki/