Introduction

The Polish state, reborn in the aftermath of World War I, was facing great challenges (for background on the re-establishment of Poland in 1918, see A. Grebieniow and J. Rudnicki in this series). Among them was the need to build a new system of administration. This was primarily a matter of establishing and organising a modern central and local government administration. To operate efficiently, this administration had to be subjected to external control. The latter was to protect individuals and legal entities in their dealings with the administration, which was one of the basic prerequisites for fostering the rule of law. Therefore, by virtue of the 1921 Constitution of the Republic of Poland, the Supreme Administrative Tribunal was established – this was the main court controlling the administration in the Second Republic of Poland until 1939 (see Ustawa z dnia 17 marca 1921 r. – Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej). Thus, the concept of judicial control over administrative decisions became one of the main tenets of the political system in the Second Republic of Poland, reborn after 1918. When establishing the new administrative judiciary, reference was made to the latest achievements of Western European legal traditions, especially doctrines fostering the rule of law. This can be seen as one of the greatest achievements of the Polish judicial and administrative practice in the Interwar period.

The political and legal history of the Second Republic of Poland, which functioned from 1918 to 1939, is complex. Initially, Poland started walking on a path towards democracy; however, it quickly turned towards authoritarianism. Until 1926, that is, until the so-called May coup, which was orchestrated by Józef Pilsudski, there had been an attempt to build a democratic, law-governed state with a dominant role played by parliament. Subsequently, authoritarian governments came to power in Poland – they were symbolised by the so-called “rule of the Sanation movement” and the Constitutional Act of 23 April 1935 (see Ustawa Konstytucyjna z dnia 23 kwietnia 1935 r.). Thus, these processes dominated the debate about the state and the law at that time. Nevertheless, the judicial control over administrative decisions, which was carried out by the Supreme Administrative Tribunal (Najwyższy Trybunał Administracyjny – NTA, hereinafter called the NTA), established in 1921, remained in place throughout that period.

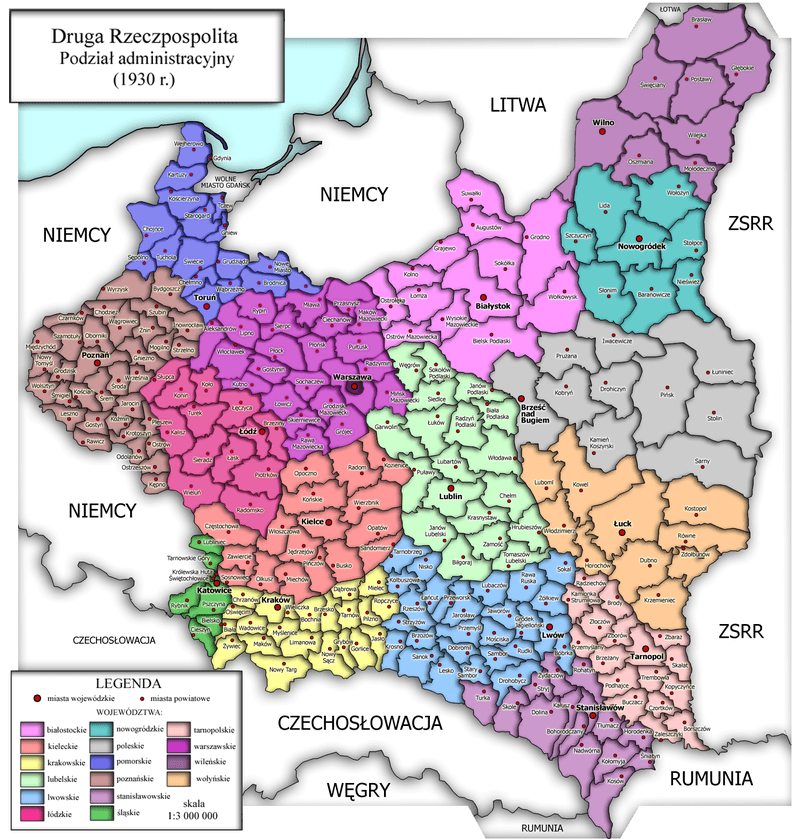

The Consequences of the Partition of Poland

Before discussing the role of the NTA, it should be mentioned that the administrative judiciary on Polish land had operated in the Prussian and Austrian partitions before World War I. This meant that both the so-called North German model of administrative judiciary and the so-called South German model of administrative judiciary were in place there. Under the former, specific to the Prussian partition, the hierarchical structure of administrative judiciary was as follows: district (city) departments, regional departments and the Higher Administrative Court in Berlin. Accordingly, the control of the legality of administrative actions was carried out by independent and collegial administrative bodies, operating in accordance with the rules of judicial procedure (see Gesetz uber die allgemeine Landesverwaltung, Gesetz-Sammlung 1883, p. 155; Gesetz über die Zuständigkeit der Verwaltungs- und Verwaltungsgerichtsbehörden, Gesetz-Sammlung 1883, p. 237; A. Tarnowska, Sądownictwo administracyjne II RP a pruski model sądownictwa administracyjnego, „Studia z Dziejów Państwa i Prawa Polskiego” 2006, Nr 2, p. 418).

Thus, the administrative judiciary was not separated from the administration itself. The main goal of the Prussian system, in contrast to the South German model, was to protect the implementation of the objective legal order in the process of applying the law by the administration, and not to protect the public subjective rights of the individual. Therefore, the administrative judiciary served more as an element of the state’s control over the administration than as an instrument for protecting citizen rights. By contrast, the second model, applied in Austria-Hungary under the Act of 22 October 1875, was based on a single-instance Administrative Tribunal located in Vienna that ruled on a nationwide basis. The essence of the Austrian Administrative Tribunal’s role was to hear disputes over violations of subjective rights by rulings issued by central and local government bodies. In addition, the French model of administrative judiciary was in place in the Duchy of Warsaw and the Kingdom of Poland. All this shows that before November 1918 various models of judicial control over the administration coexisted on Polish lands.

Towards Establishing the NTA

All of the above-mentioned factors had an impact on the decision to establish an administrative judiciary in the Polish state reborn after 1918. However, the greatest influence on the creation of the new judiciary was exerted by supporters of the Austrian model, who had experience working at the Austrian Administrative Tribunal in Vienna before 1918. Judge Jan Sawicki, in particular, played an important role in these discussions. Therefore, Article 73 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 17 March 1921 stated:

A separate act will establish an administrative judiciary, based in its organisation the cooperation between the civic and judicial representatives headed by the Supreme Administrative Tribunal, to adjudicate on the legality of administrative acts with respect to both the central and the local government administration.

The role of the administrative judiciary, introduced at this time, was to exercise control over the central and the local government administration with regard to the legality of administrative acts. It was to be based on a combination of professional or judicial representatives with social, civic representatives. However, the constitutional phrase “headed by the Supreme Administrative Tribunal” suggested that the administrative judiciary would function at least as a two-instance system.

As a consequence, the Act of 3 August 1922 on the Supreme Administrative Tribunal (the NTA Act) was adopted (see Ustawa z dnia 3 sierpnia 1922 r. o Najwyższym Trybunale Administracyjnym). According thereto, the NTA’s competence to rule on the legality of administrative acts was based on a general clause. However, the general clause, which constituted the basis of the NTA’s attribution, enumerated a number of cases exempt from the review of the legality by this judicial body. For example, excluded from the NTA’s jurisdiction were: cases in which the administrative authorities had the authority to take decisions at their discretion, within the limits of such discretion; cases related to appointment to public offices and positions, as long as it did not involve a violation of the right reserved by law to fill them or present candidates; cases concerning military operations, organisation of armed forces and mobilisation, except for cases related to supplying and replenishing the army; and disciplinary cases.

As for the structure of the administrative judiciary, the NTA Act of 1922 indicated that until the establishment of a lower-level administrative judiciary on the entire territory of the Republic of Poland, the NTA would be a single administrative court. In practice, the lower-level administrative courts were functioning only in the former Prussian partition. This meant that outside the territory of the former Prussian partition, Poland, for a temporary period, adopted the so-called Austrian model of administrative judiciary. Its adoption, however, was met with criticism by legal scholars. In this regard, Dorota Malec, a Polish researcher, has observed that:

This is because the model adopted by Parliament did not satisfy most specialists. Furthermore, it was considered as a temporary solution, which in no way prejudiced the validity of the proposed concepts of developing a multi-instance administrative judiciary (D. Malec, Koncepcje organizacji sądownictwa administracyjnego w Polsce w okresie międzywojennym, [w:] Dzieje wymiaru sprawiedliwości, (Concepts of organizing administrative judiciary in Poland in the interwar period, [in:] History of Justice), edited by T. Maciejewski, Koszalin 1999, p. 327).

The Decree of the President of the Republic of Poland of 27 October 1932 on the Supreme Administrative Tribunal, which replaced the 1922 Act on the NTA, did not change this state of affairs. That is why, it was criticised. It was pointed out, in particular, that the text of the new Act had practically neither been consulted with representatives of legal scholarship, nor with practising lawyers. And again, as in 1922, there were calls for the establishment of lower levels of administrative judiciary.

In connection with the above, in 1934, Antoni Chmurski, a Polish jurist, asserted that “the legal world and society were practically taken by surprise by the reform” (A. Chmurski, Reforma Najwyższego Trybunału Administracyjnego, (Reform of the Supreme Administrative Tribunal), Warsaw 1934, p. 48). In addition, Chmurski noted that regulating the NTA’s constitutional position by way of a decree of the President of the Republic of Poland “raises serious concerns” since this regulation was issued by the executive branch, while, after all, the essence of the administrative judiciary is to exert control over the actions of this branch. The author concluded that the NTA’s position under the 1922 Act was based on the principle of independence, while the NTA’s position set forth in the 1932 decree was an expression of authoritarianism, which Chmurski called the “position of authority”. In 1935, Chmurski explicitly claimed that Poland’s judiciary, both administrative and general, was subordinated to the executive branch of government (A. Chmurski, Nowa Konstytucja, (New Constitution), Warsaw 1935, p. 8.). The authoritarianism towards the administrative judiciary was based on three factors:

1) subordinating the NTA to the executive branch, in accordance with the hierarchy, which was expressed in the fact that the Prime Minister “became the Tribunal’s supervisor”;

2) ensuring the predominance of the administrative representatives over the judicial representatives in the composition of the NTA;

3) curtailing the independence of the Tribunal’s judges and the ability to remove them (A. Chmurski, Reforma Najwyższego Trybunału Administracyjnego, (Reform of the Supreme Administrative Tribunal), Warsaw 1934, pp. 49-50). In this context, Chmurski pointed out that the process of subordinating the NTA to the executive branch had already begun when the decree of 7 February 1928 was issued (Journal of Laws no. 13, item 94).

The changes to the law introduced after 1926 were related to the broader process of political change taking place in pre-WWII Poland. The Sanation movement, after it had taken over power as a result of the so-called May Coup of 1926, was seeking to introduce legal changes, involving the significant strengthening of executive power, to Poland’s political system. The result of these trends was the enactment of a new constitution, the Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 23 April 1935. It devoted even less space to the administrative judiciary than the 1921 Constitution. Its Article 70, section 1, clause b, indicated that: “The Supreme Administrative Tribunal shall be established to rule on the legality of administrative acts”. Such a brief provision may have indicated the reluctance of the ruling elite to expand the existing system of judicial control over the administration. Nevertheless, the NTA itself was preserved.

The Lights and Shadows of the NTA

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 brought an end to the NTA’s existence. Despite difficulties of organisational and normative nature, the case law of the NTA during the Interwar period should be viewed positively. The NTA constituted an important element of the country’s political system tasked with guaranteeing compliance with the law. Its importance in the system should also be remembered due to the fact that there was no institution to control the constitutionality of laws in the Second Republic of Poland. The Tribunal’s case law contributed to shoring up and developing the rule of law in the activities of Poland’s government administration, among other things by influencing the interpretation and application of the law on administrative procedure by public administration bodies. This was extremely important as the establishment of the NTA provided protection for citizens in individual cases against violations of the law by the Polish administration, which was taking shape after the difficult period of Poland’s partition. Pre-WWII practising lawyers Mieczyslaw Baumgart and Henryk Habel wrote in their commentary on the 1932 NTA that the NTA “constitutes the most serious guarantee of the rule of law in Polish public administration” (the text of the Supreme Administrative Tribunal Act and the Administrative Procedure Act (as to the Act on the Tribunal – the text in force since 15 November 1932, and the previous text), the detailed case law of the Administrative Tribunal with respect to its competence and proceedings as well as administrative proceedings, the executive and trade union regulations, commentary and index, compiled by Mieczysław Baumgart and Henryk Habel, Warsaw 1933, p. 5).

One can, of course, object this view and subscribe to the opinion of some critics of the existing NTA provisions that, following the Austrian models (conceptually inspired from the Austrian Administrative Tribunal, which had been established in 1875), the 1922 Act and the 1932 Decree on the NTA did not expand the administrative judiciary by introducing lower instances than the NTA. Also, the NTA grappled with the problem of protracted proceedings and a frequent failure of administrative bodies to enforce its rulings. However, given the rather limited capacity of the state after such a long period of partition, the resulting diversity in the state’s territory, the shortfall of qualified personnel and, most importantly, the authoritarian tendencies in the process of the state system’s evolution, it should be concluded that the NTA fulfilled its role.

The NTA and the Idea of Administrative Judiciary after WWII in the People’s Republic of Poland

In addition, the existence of the administrative judiciary in the Second Republic of Poland was strongly solidified in legal scholarship pertaining to judicial studies. Hence, the need for a functioning judicial control over government administration in the state system that, starting from 1944 – i.e. in the period of the post-WWII reconstruction of the Polish state – and the question of establishing the administrative judiciary subsequently reemerged in the discussion on the future of Poland’s legal system. This was particularly evident in the period 1945-1948. Although the communist authorities abandoned the idea to reactivate the NTA immediately after the war, as well as the plan to introduce another body that, as an administrative court, would consider complaints against administrative decisions of the government administration, the memory of the NTA did not die out in the People’s Republic of Poland. Indeed, some experience related to the NTA was used in establishing the Supreme Administrative Court in the late 1970s and early 1980s. That is why the Supreme Administrative Court celebrated the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the NTA in 2022.

Therefore, it can be rightly asserted that the functioning of the NTA and its body of case law constitute an important contribution not only to the history of Polish law, but also to the history of administrative law in Central and Eastern Europe in general.

Posted by Dr Michał Patryk Sadłowski, Department of History of Administration, Faculty of Law and Administration, University of Warsaw

This piece belongs to Season 2 of the “Cross-jurisdictional dialogues in the Interwar period” series dedicated to less-known legal transfers which have had a palpable impact on the advancement of the law. The Interwar period was a time of disillusionment with well-established paradigms and legislative models, but also a time of hope in which comparative dialogue and exchange of ideas between jurisdictions thrived. The series is edited by Prof Yseult Marique (Essex University) and Dr Radosveta Vassileva (Middlesex University). To access the other pieces from this series, either select the ‘Interwar Dialogue’ category or click on the #Series_Interwar_Dialogue tag on the BACL Blog.

Suggested citation: Michał Patryk Sadłowski, “The Role of Administrative Justice before WWII in Poland”, BACL Blog, available https://british-association-comparative-law.org/2024/06/07/the-role-of-administrative-justice-before-wwii-in-poland-by-michal-patryk-sadlowski/

2 Comments

Comments are closed.