1 Statutory Reform: the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008

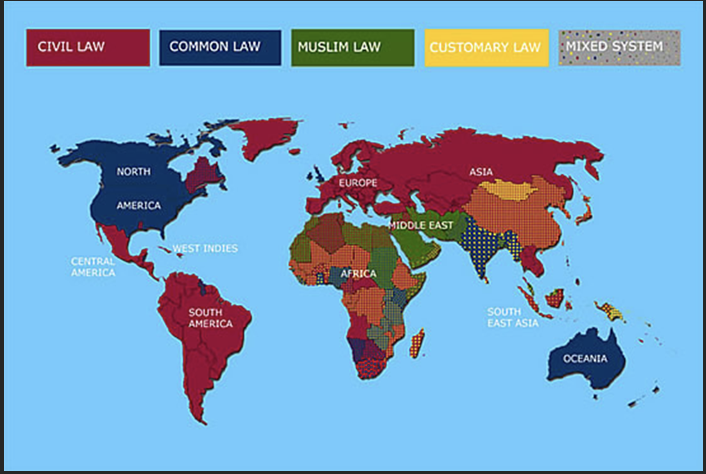

The South African law of obligations is ‘mixed’, albeit in rather unequal parts. Most of its general principles derive from the civil law tradition, but there have also been notable common law influences, and, more recently, signs that indigenous customary law may enhance its further development. Rather unusually for a system with such strong roots in the civil law tradition, the South African law of obligations, and indeed most of private law in this jurisdiction, remains uncodified. It is therefore the task of the courts to set out and develop the general principles of the law of obligations. This must be done within the broader context of a constitution containing a horizontally applicable bill of rights, which does not only require of courts to ensure that the non-statutory law meets constitutional demands, but empowers the courts to strike down legislation that fails to do (see here).

Mixed Legal Systems of the world; Picture credits: University of Ottawa

It is against this very brief overview of the legal system that we turn to the topic at hand, namely the reaction of the South African courts to the most profound recent legislative intervention in the law of obligations, and more specifically in the law of contract, namely the Consumer Protection Act 68 of 2008. That such a radical intervention was long overdue, and was crucial to improve the lot of millions of consumers, most of whom were the victims of a system that perpetuated severe inequality, cannot be doubted. But, unfortunately, not much positive can be said of the way in which the CPA was adopted. It is a rather crude amalgam of earlier local legislation and eclectically selected foreign statutory consumer law, with the Australian, Canadian and EU influences being particularly strong (see J Barnard, “The role of comparative law in consumer protection law: A South African perspective” (2017) 29 SA Merc LJ 353). It is also characterised by some rather idiosyncratic drafting, which often does not reflect a proper understanding of the broader legal context in which the CPA had to be applied. To say that there is little discernible indication that the legislature took into account local solutions developed in the case law would be an understatement.

2 The Judicial Response

2 1 The response to the courts being the last resort: section 69(d) CPA

How then did the South African courts respond to the CPA? The answer may be divided into two parts. The first part concerns the courts’ reaction to section 69, a key provision in the CPA that sets out the role of the courts in its enforcement. In subsections (a) to (c), and in no discernibly logical sequence, it lists various entities that the consumer may approach to enforce the rights granted by the Act. These entities include administrative bodies (most notably the National Consumer Commission, National Consumer Tribunal, alternative dispute resolution agents, and regional consumer courts), and ombuds established by the private sector (most notably the Consumer Goods and Services Ombud). Finally, subsection 69(d) deals with the ordinary courts, but crucially for present purposes, states that these courts may only be approached ‘if all other remedies available to that person in terms of national legislation have been exhausted’.

In theory, placing the courts at the end of a hierarchy of institutions may perhaps be defended on the basis that it is preferable first to try and resolve consumer disputes through affordable, less adversarial means. But the combination of bad drafting, which makes it uncertain exactly which avenues must be followed in approaching these institutions, and when these avenues are exhausted, as well as the practical reality that some of the institutions are dysfunctional, have undermined the benefits of placing the courts last in the queue. It may in any event from the outset not have been a good idea to prevent direct access to the Small Claims Courts, which are affordable, widespread, and also follow less adversarial procedures than the other civil courts (on the South African court system, see generally here)

Given the desirability of overcoming this severe limitation on access to the courts, how did they react to it? In essence, this is a matter of interpretation. And here the courts were aided by section 4(3) of the CPA, which reads as follows:

‘If any provision of this Act, read in its context, can reasonably be construed to have more than one meaning, the Tribunal or court must prefer the meaning that best promotes the spirit and purposes of this Act, and will best improve the realisation and enjoyment of consumer rights ….’

However, in Joroy 4440 CC v Potgieter NNO 2016 (3) SA 465 (FB) the court made short shrift of the notion that this provision could aid consumers: section 69(d) was held to be unambiguous in stating that the courts were last in the queue. This interpretation was even justified on constitutional grounds, by relying on the judgment of the Constitutional Court in Chirwa v Transnet Ltd 2008 (4) SA 367 (CC), which essentially held that parties must pursue their claims primarily through specialised frameworks created for the resolution of disputes.

Joroy clearly does not display signs of judicial creativity or innovation. But this position changed drastically with the Supreme Court of Appeal judgment in Motus Corporation (Pty) Ltd v Wentzel [2021] ZASCA 40. Although not required for purposes of the dispute to pronounce on the operation of section 69, the court made it very clear that it is not pleased with the potentially detrimental impact of section 69 on the right of access to the courts.

‘[26] … The issues arising from the section will need to be resolved on another occasion. It suffices to say that the primary guide in interpreting the section will be s 34 of the Constitution and the guarantee of the right of access to courts. Section 69(d) should not lightly be read as excluding the right of consumers to approach the court in order to obtain redress…

[27] The section is couched in permissive language consistent with the consumer having a right to choose which remedy to pursue. Those in (a), (b) and (c) appear to be couched as alternatives and, as already noted, there is no clear hierarchy. … Furthermore, subsec (d) does not refer to the consumer pursuing all other remedies ‘in terms of this Act’, but of pursuing all other remedies available in terms of national legislation. That could be a reference to legislation other than the Act, or to the remedies under both the Act and other applicable consumer legislation … Given the purpose of the Act to protect the interests of the consumer, … there is no apparent reason why they should be precluded from pursuing immediately what may be their most effective remedy. Nor is there any apparent reason why the dissatisfied consumer who turns to a court having jurisdiction should find themselves enmeshed in procedural niceties having no bearing on the problems that caused them to approach the court.’

The Supreme Court of Appeal of South Africa; Picture Credits: Wikipedia

Thus, we essentially are provided with a judicial declaration of intent from the second highest court that section 69 ought to be applied in a manner that is more conducive to enabling access to the courts. Unsurprisingly, some subsequent High Court judgments, such as Khoza v Ifa Fair-Zim Hotel and Resort (Pty) Ltd (D3385/2023; D6433/2023) [2024] ZAKZDHC 45 (4 July 2024) and Steynberg v Tammy Taylor Nails Franchising No 45 (Pty) Ltd (Case No 23655/2021, Gauteng Division, Pretoria, 21 June 2022) have acted on this declaration. Thus, in Steynberg it was expressly stated that ‘although, on the face of it, the ruling in Motus Corporation in relation to section 69 was said to be obiter, the reasons set out in the judgment are authoritative and they carry considerable weight’ (para 22). However, a handful of unreported judgments hardly constitute a strong enough foundation for future legal development. Ultimately, if the progressive position favoured in Motus is to be consolidated, the legislature would have to intervene and effect an appropriate amendment to section 69, or the Constitutional Court would have to pronounce definitively on its constitutionality.

2 2 The response to changes in substantive law: fairness control under section 48 CPA

The second part of the judicial response to the CPA deals with the substantive rights it accords consumers. It may be fair to say that the courts have generally played a rather limited role in developing the law relating to these rights. For present purpose, let us just briefly consider one example, namely section 48, a provision of the CPA that may potentially have made the greatest inroads into the law of contract. In essence, section 48 allows courts to control the terms or price of a consumer contract according to the standard of fairness.

One may be forgiven for expecting that the inclusion of this section in the CPA would have caused considerable uncertainty and widespread litigation from consumer seeking to escape inequitable or harsh terms. But the response has been surprisingly muted. The Constitutional Court in Hattingh v Juta 2013 (3) SA 275 (CC) recognised the existence of section 48, but merely by mentioning in passing that ‘the movement towards the infusion of justice and equity or fairness into certain legal relationships’ was also taken further in this provision.

Perhaps more significant in the context of the present enquiry into judicial activism, or lack thereof, is the rare, but more detailed consideration given to section 48 in the High Court judgment of Magic Vending (Pty) Ltd v Tambwe 2021 (2) SA 512 (WCC). In essence, the court was unwilling to rely on this section to invalidate a contractual clause entitling termination due to breach of contract, and interpreted it as follows:

‘[8] I do not consider that the provisions of the Consumer Protection Act should be construed so as to purport to invest in the courts a power to refuse to enforce contractual terms on the basis that their enforcement would, in the judge’s subjective view, be unfair, unreasonable or unduly harsh; they should rather be construed as, in certain respects, codifying the established principle that courts will refuse to enforce contractual provisions that are so unfair, unreasonable or unjust that it would be contrary to public policy to give effect to them.’

Thus, instead of being a radical innovation, section 48 could on this interpretation merely amount to a ‘codification’ of the test already used in the common law to regulate contractual terms, namely that their content or enforcement should not be so unfair as to be against public policy. But when would this be the case? There is considerable uncertainty as to what the court meant with the qualification that section 48 is only in ‘certain respects’ a codification. This qualification is vital in establishing whether the legislature provides greater protection than the common law, which is what section 48 may be understood to have done, or whether Magic Vending has subtly and creatively subverted this provision’s transformative power. Again, we await further judicial clarification.

3 Conclusion

In Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story, The Adventure of Silver Blaze, Sherlock Holmes observed that a dog did not bark at night-time, when it would have been expected to do so. Similarly, it may be asked why South African courts have been so silent on the CPA, given the vast inroads that it has made on the common law of contract. This stands in marked contrast to the courts’ constant and far-reaching engagement with the National Credit Act 34 of 2005 (NCA), the other more recent major legislative intervention in the law of contract. There the dog barked often and loudly. The NCA litigation was driven by a variety of factors, which include problematic drafting, as well as large financial institutions being willing to resort to litigation to promote their interests. But the CPA also is not a model of legislative drafting, and it also affects institutional parties with deep pockets. Ultimately, the most important explanation for the different judicial reaction appears to be the most obvious one we encountered above: the formidable procedural hurdle that section 69 of the CPA placed in the way of parties by relegating the courts to the last resort for relief.

However, as we have also seen, the position may well change. The judiciary is increasingly willing to interpret this provision more generously in terms of allowing judicial access, and are critical of its potential conflict with the fundamental right of access to the courts. Ultimately, the legislature may be compelled to amend section 69 and provide the consumer greater freedom in terms of the choice of institutions to approach for relief under the CPA. And this may in turn give the courts greater opportunity to give meaning and effect to the substantive rights that it contains.

Posted by Jacques du Plessis, Distinguished Professor of Law, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

This piece belongs to BACL’s “Judicial Creativity” series which shines a light on the role of judicial creativity in recent reforms of the laws of obligations around the world. The series is edited by Dr Radosveta Vassileva (Middlesex University), Dr Sirko Harder (University of Sussex), and Prof Yseult Marique (University of Essex). To access the other pieces from this series, either select the “Judicial Creativity and the Law of Obligations” category or click on the #Judicial Creativity & Obligations tag on the BACL Blog.

Suggested citation: J du Plessis, ‘South African Statutory Consumer Law and the Courts: The Curious Case of the Dog That Did Not Bark’, BACL blog available at https://british-association-comparative-law.org

1 Comment

Comments are closed.