Introduction

There is constant friction between the stability of the law and the needs of practice. Civil codes are laws made to last for centuries to give stability and certainty; however, they come at the cost of lack of flexibility and outdatedness of the law. Therefore, if a new phenomenon arises that disrupts the law such as artificial intelligence, climate change, gender rights, among others, the legislator needs to update the law. However, legislative reform must follow a formal process to define the best general rules, which is often long and complicated for political reasons. Faced with such obstacle, the task falls to judges.

If a specific case occurs where it is found that there is no law or the law is inadequate, the judge may innovate to find a solution. In the civil law tradition, the judge – although it is highly debatable and will depend on the applicable law – would create a rule for the case to fill a legal gap or improve the law. In this way, a general rule within the civil code remains stable and is only supplemented by judicial work.

However, not every case of judicial creativity is a success story. There are instances where it has been deemed that the judge has provided a proper ruling, such as the modification of contract in view of change of circumstances caused by war. The German Civil Code (BGB) originally did not have a legal provision on hardship, and the courts invoked the concept of Treu und Glauben (good faith) in § 242 BGB for this purpose. This experience served as a basis for the German legislator to later incorporate § 313 BGB on Störung der Geschäftsgrundlage (failure of the basis of the transaction) (see Basil S Markesinis, Hannes Unberath and Angus C Johnston, The German Law of Contract. A Comparative Treatise (2d edn, Hart Publishing 2006), specifically Ch 7), as well as a guide for other jurisdictions in Europe and Latin America for the incorporation of hardship in legislation. For instance, one can consider article 1238 of the Proposal for the Modernisation of the Spanish Civil Code on Obligations and Contracts (2023). It states that hardship occurs if the basis of the transaction changes and it is not reasonable to require the affected party to still perform the contract under its original terms. Likewise, German case law and scholarship is extensively studied in Latin American jurisdictions in a debate concerning the reform of hardship and even the incorporation of the English doctrine of frustration of purpose (see Sergio Garcia Long, ‘While English lawyers say no, civil lawyers say yes. The intriguing case of frustration of purpose in comparative law’ (2023) 31 European Law Review 979).

In contrast, there are other cases where one can argue that the judge erred in judicial innovation. This happened with the Peruvian judges’ creation of punitive damages in case law. At the time, some Peruvian courts considered it necessary to create –literally, to create – punitive damages in employment law; however, they did so by going beyond their inherent powers and by violating constitutional provisions pertaining to the separation of the powers in the State as well as the rules applicable to all penalties, as explained below. Consequently, this conception of punitive damages was overturned by later Peruvian judges.

This experience demonstrates the interplay between legal innovation and the powers of the judge. Above all, from a comparative perspective, the mistake made can serve as an example of importing common law conceptions, such as punitive damages, into a civil law system that has gone wrong.

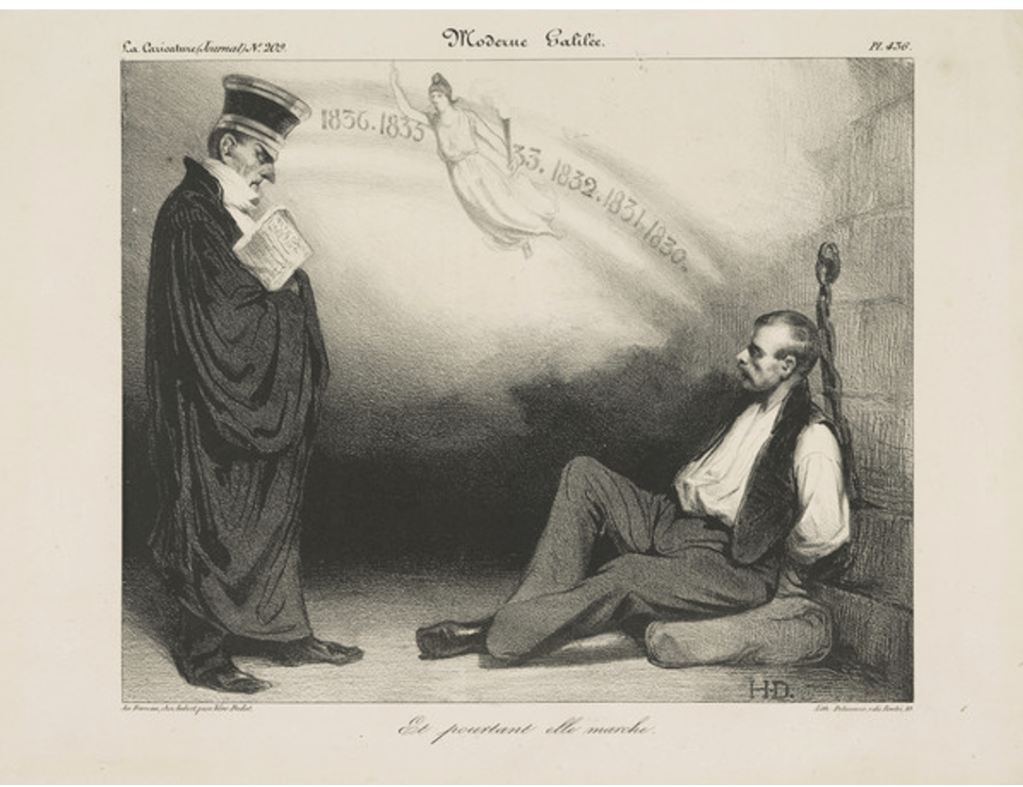

‘A Modern Galileo: And Yet It Moves’ by Honoré Daumier; Picture credits: Creative commons CC by NC

Peruvian Punitive Damages and the Forgotten Debate

In October 2016 and December 2017, the V and VI Supreme Jurisdictional Plenary in Labour and Social Security Matters were published in Peru. In these Plenaries, employment judges created punitive damages (see Sergio Garcia Long, ‘Daños punitivos en Perú’ (2018) 50 Actualidad Jurídica Uría Menéndez 162). A jurisdictional plenary session is a meeting of judges whose purpose is to reach an agreement on how to resolve a problematic case, and thus, achieve harmonisation of case law. Later judges, when deciding a case, may deviate from the plenary agreement if they explain their reasons. Jurisdictional plenary sessions are permitted under article 116 of the Unified Text of the Organic Law of the Judiciary.

On this occasion, the Peruvian judges focused on compensation for wrongful and fraudulent dismissal, and working accidents under Peruvian law. In an attempt to strengthen worker protection against companies, judges stated that workers could seek punitive damages even if there was no statute to allow it.

The V Plenary pointed out that punitive damages (a) can be awarded in the case of wrongful and fraudulent dismissals, (b) can be awarded ex officio, (c) are limited to the amount the worker has not contributed to the pension system, and (d) can be awarded on the basis of an extensive interpretation of the notion of non-pecuniary loss or “daño moral” under the Peruvian Civil Code (see articles 1322 and 1985).

The VI Plenary stated that punitive damages (a) can be awarded in the case of work-related accidents, (b) can be awarded ex officio, and (c) are limited to the amount awarded for compensatory damages.

These Peruvian-style punitive damages skipped a fundamental question, which is the starting point of the debate in comparative literature: are punitive damages compatible with civil law? (see Helmut Koziol, ‘Punitive damages – A European Perspective’ (2008) 68 Louisiana Law Review 741). Concerns include (see my book Sergio Garcia Long, La función punitiva en el derecho privado (PUCP 2019), specifically Part II Ch 2) the strict division between private law and criminal law, the dogma of compensation (particularly, see René Demogue, ‘Validity of the theory of compensatory damages’ (1918) 27 Yale Law Journal 585), and the prohibition of unjustified enrichment, among others.

Punitive damages are not incompatible with civil law per se, and this can be seen in the case law on the exequatur of punitive damages (see Cedric Vanleenhove, Punitive damages in private international law. Lessons for the European Union (Intersentia 2017), specifically Ch 4) in various countries such as Greece, Switzerland, Spain, France and Italy, where it has been pointed out, in summary, that public policy can only be used to reject the sanction if it is disproportionate. Likewise, in France there were several proposals for reform (see Solène Rowan, ‘Punishment and private law: Some comparative observations’ in Elise Bant, Wayne Courtney, James Goudkamp and Jeannie Marie Paterson (eds), Punishment and private law (Hart Publishing 2021) 63) which suggested incorporating punitive damages in the Code civil such as Catala 2005 (art. 1371), Béteille 2010 (art. 1386-25), Terré 2011 (arts. 54 and 69) and Projet de Réforme de la Responsabilité Civile 2017 (art. 1266-1). This shows that the hostility towards punitive damages has steadily been disappearing.

I have explained in detail in my book why the above development is due to the evolution of punitive damages in the US (Sergio Garcia Long, La función punitiva en el derecho privado (PUCP 2019)). Previously, punitive damages were unpredictable in relation to their availability and amount under § 908 of the Restatement (Second) of Torts. In addition, the penalty was paid to the victim, who could be deemed to be unduly enriched.

However, punitive damages have evolved in both common and civil law jurisdictions, and some jurisdictions have developed limitations on them (see the national reports in Helmut Koziol and Vanessa Wilcox (eds), Punitive damages: Common Law and Civil Law Perspectives (Springer 2009)): (i) it is preferred that they be awarded in specific cases and not generally when the jury or court deems it appropriate, (ii) there are limitations in the form of multiple damages or caps, and (iii) the penalty is no longer paid in full to the victim, but instead, the payment is distributed partly or entirely to other stakeholders (government, compensation fund, lawyers, etc.).

Therefore, the “new” punitive damages are not alien to the civil law. For example, the Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China – here I consider Chinese law as part of the civil law tradition as argued by other authors (see Chen Lei, ‘The historical development of the Civil Law tradition in China: A private law perspective’ (2010) 78 The Legal History Review 159)– has recently incorporated them for intentional conduct relating to defective products, environmental damage and violations of intellectual property (arts. 179, 1185, 1207 and 1232).

As Peruvian judges were unaware of the debate and development of the notion of punitive damages in the US and other relevant civil law jurisdictions, they incorporated punitive damages in a controversial way, and this provoked the reaction of later courts. For example, in Cassation No. 464-2018-La Libertad (see Sergio Garcia Long, ‘Casación 1 – Daños punitivos 0. Comentario a la Casación N° 464-2018-La Libertad’ (2021) 101 Gaceta Civil & Procesal Civil 153), the appellate court of La Libertad noted that compensatory damages could be increased to punish the defendant. In response, the defendant asked the Supreme Court to overturn the judgment for awarding hidden punitive damages, which do not exist under Peruvian law, i.e., there is no statute permitting them. The Supreme Court agreed and stated that punishment is incompatible with the Peruvian notion of civil liability and, consequently, awarding punitive damages violates the principle of legality, the right to defence and due process. Strictly speaking, it should be understood that there are no punitive damages by statute rather than say that punishment is incompatible because it does exist under Peruvian private law: for instance, in the possibility of increasing the amount of damages for breach of contract based on the degree of fault and the validity of penalty clauses (see articles 1321 and 1341-1342 of the Peruvian Civil Code).

Subsequently, in October 2020, the Conclusions of the II Plenary Jurisdictional District Court in Labour and Labour Procedural Matters of Lima were issued according to which it is unconstitutional to award punitive damages for cases of wrongful and fraudulent dismissal unless they are recognised by law. Finally, and similarly, in Cassation No. 9579-2019-Lima the court ruled that punitive damages cannot be awarded in Peru because there is no law allowing them (see Leysser León, ‘Adios a los punitive damages a la peruana (pero sin desconocer la función punitiva de la responsabilidad civil)’ (2024) 117 Actualidad Civil 5).

So, as the court found an error and corrected it, important lessons remain. In general, it was right for Peruvian case law to recognise that punitive damages were incorrectly created. However, it does not mean that punitive damages are incompatible with Peruvian law per se. The error is one of form, not of substance.

Overall, the error serves to identify how punitive damages should be correctly incorporated into a civil law jurisdiction. Namely, there are constitutional limits that prevent courts from creating sanction mechanisms, which were ignored by Peruvian courts.

Separation of Powers

Peru has embraced the French notion of the separation of powers. In the French legal system, the legislator creates the law while the judge applies it. The judge is the bouche de la loi (the mouth of the law). Certainly this is an over generalisation (see Peter Stein, ‘Judge and jurist in the Civil Law: A historical interpretation’ (1985) 46 Louisiana Law Review 241) since civil law judges can make law for the case in question as German judges did with hardship, but the civil law judge does not have the broad powers of the common law judge (the oracles of the law) where there is a system of precedent (see John P. Dawson, The Oracles of the Law (University of Michigan Law School 1968), specifically Ch 1).

For instance, in Germany there was Aktenversendung (sending the file) until 1878 (see R.C. van Caenegem, European law in the past and the future. Unity and diversity over two millennia (Cambridge University Press 2001) 45-46). This was a type of process where the judge could send the file of a difficult case to a law school to be decided by professors applying Roman law as if it were an appellate court. Judges felt more confident when they could rely on the opinion of prominent professors. Quite rightly so, Merryman explained that in the civil law the surnames of the law professors are well known (Domat, Pothier, Planiol, Savigny, Ihering), while in the common law the surnames of the judges are famous (Holmes, Cardozo, Brandies, Coke, Mansfield, Blackburn) (see John Henry Merryman, The Civil Law Tradition. An introduction to the legal systems of Europe and Latin America (3rd edn, Stanford University Press 2007) 72-73).

Also, if one reads a civil law book on contracts, one will find lots of references to publications by law professors and little case law, whereas if one reads – for instance – the chapter on frustration from Hugh Beale (general editor), Chitty on Contracts (35th, Sweet & Maxwell 2024) one will find pronouncedly more references to case law than to scholarly writing compared to the typical textbook in civil law systems. Based on my own experience, this difference is noted by international postgrad students studying in the UK after being trained at a university in a civil law jurisdiction.

The context explained has certainly changed over time, with grey areas or blurred lines and the risk of over simplification. Civil Law judges are not just the mouth of the law. However, it serves as a background for understanding the role played by judges and professors in the common law and the civil law. In certain jurisdictions such as Peru, the tradition is very strong and remains unchanged over the years.

The Political Constitution of Peru has provisions on the division of powers and assigns the creation of the law to the legislator through different formal processes according to the hierarchy of the sources of law (see for instance articles 90-119 on the structure of the state). There is no constitutional provision allowing the judge to create sanctions. Although the Peruvian Civil Code has embraced the notion of contractual good faith which could give the judge some leeway to modify or supplement the contract (see article 1362), this prerogative cannot be exercised to the point of creating sanctions that must comply with constitutional provisions that have a higher rank than the law.

Judicial Limits to the Creation of Sanctions Mechanisms by Courts

Criminal sanctions must respect some fundamental principles: (i) no punishment without law (nullum crimen, nulla poena, sine lege), (ii) proportionality, and (iii) prohibition of duplicity of sanctions (non bis in idem).

In the past, it was questioned whether such principles would be applicable to punitive damages. Today, this question seems to have been resolved. Above all, punitive damages are not strictly private but hybrid in that they pursue public purposes in private litigation, such as general deterrence. Hence they have also been referred to as ‘crimtorts’ (see Thomas Koenig and Michael Rustad, ‘“Crimtorts” as corporate just desert’ (1998) 31 University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform 289). Punitive damages, then, being a sanction, must comply with the principles applicable to all penalties.

Firstly, a civil law court may be able to modify the contract in the face of changed circumstances even if there is no statutory provision allowing it. However, it is different when the object of judicial creativity is a penalty. When it comes to punitive damages, a basic rule must be complied with: there is no penalty unless an enacted law so provides. This rule often has a constitutional basis, and is even recognised in international human rights instruments such as Article 7 “No punishment without law” of the European Convention on Human Rights and Article 9 “Freedom from Ex Post Facto Laws” of the American Convention of Human Rights “Pact of San Jose, Costa Rica”.

Secondly, one of the features that have frightened civil lawyers is the high amount of punitive damages that could be awarded. However, civil law jurisdictions may develop a rule of proportionality to avoid excessive awards, considering that even the US Supreme Court has required proportionality (using the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment); see BMW of North America v Gore and State Farm Mutual Automobile v Campbell.

Thirdly, multiple penalties for the same act should be avoided. The same conduct could receive a civil, an administrative and a criminal sanction. If the defendant has already been previously sanctioned, punitive damages would not be appropriate or only in a lower amount.

In summary, courts cannot create sanctions mechanisms. They must be created by the legislature. In addition, sanctions mechanisms created by law must set limits to the amount in order to comply with proportionality, and the defendant cannot be punished more than once for the same act.

Concluding Remarks

The Peruvian experience with punitive damages constitutes a case where judicial creativity went wrong because of a failure to consider substantive aspects of the rule to be innovated. At best, several lessons can be drawn from which other jurisdictions could learn.

Courts in Europe and Latin America generally do not have the legitimacy to create sanctions, but the legislature does. Therefore, judges cannot agree to create sanctions for private law via plenary session, as the Peruvian judges did. The better way forward is the enactment of a law that reflects the fundamental principles applicable to all penalties. And this path should not be considered as an alien one since punitive damages are no longer incompatible with civil law jurisdictions.

Having learned from the mistakes of others, the right path for legislating punitive damages seems to have been paved.

Posted by Sergio Garcia Long, European Law Institute and Pontifical Catholic University of Peru.

This piece belongs to BACL’s “Judicial Creativity” series which shines a light on the role of judicial creativity in recent reforms of the laws of obligations around the world. The series is edited by Dr Radosveta Vassileva (Middlesex University), Dr Sirko Harder (University of Sussex), and Prof Yseult Marique (University of Essex). To access the other pieces from this series, either select the “Judicial Creativity and the Law of Obligations” category or click on the #Judicial Creativity & Obligations tag on the BACL Blog.

Suggested citation: S Garcia Long, ‘When Judicial Creativity Goes Wrong: The Case of Punitive Damages in Peru’ BACL blog 24 January 2025.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.