A striking feature of legal education lies in the way it comes to feel natural to us. We easily forget that our training is rooted in a particular time and place. We know that law differs across the United Kingdom, the United States, Japan, and France, and that these differences are substantive. It is equally true that the way law is taught varies from one jurisdiction to another. What we too rarely notice is how our legal education shapes the very categories through which we think. The result is not only that we produce different answers to similar questions, but that we often do not ask the same questions at all. What appears as a legal problem here may not even register as such elsewhere; hence what seems to me a legal phenomenon may not even be recognised as one by my neighbour. It is precisely this difficulty that I confronted at length in my doctoral research on the use of academic classifications in constitutional law. I will begin by retracing how the question first arose (I), then turn to the comparative methodology I developed in response (II) and finally offer a brief illustration of the kinds of analysis it enables (III).

I. The Genesis of the Inquiry – on multiplicity and perspectivism

I remember clearly meeting another public lawyer at McGill, at the beginning of my doctoral studies, at a conference on constitutional amendments. She had trained at Cambridge, while I had at Bordeaux. She spoke as if law were, above all, a matter of adjudication and case-law reasoning. That this view holds in the United States, in Canada, or in Britain is one thing. But what struck me was how easily the particular slid into the universal. The conversation was not framed as a reflection on constitutional amendment in common law systems, but as a reflection on constitutional amendment as such.

This small exchange had a lasting effect on my research. I was then working on the United Kingdom’s territorial constitution and the devolution of powers: was it a federation, a union-state, a unitary state, or something else entirely? But would scholars from elsewhere find such questions of interest ? I then had a shift in perspective, that opened a much more compelling line of inquiry: to what extent do our legal traditions shape not only the answers we give, but the very questions we are capable of asking?

From this vantage, my inquiry was framed as follows: how might constitutional lawyers, conceived as groups from three distinct traditions – France, the United Kingdom, and Canada – understand the British territorial constitution through the lenses of their respective training? The purpose was not to catalogue what Canadian or French scholars had written about it (in truth, very little), but to consider, in an ideal-typical sense, how each might apprehend the same constitutional object. My focus thus shifted: not only to why we classify the same object in different ways, but also to how we approach the act of classifying itself. The way we organise our legal universe often tells us more about ourselves than about what we describe. The classificatory instinct is, in this sense, a mirror: it reflects the expectations and intellectual habits of those who construct it, often more faithfully than the object it seeks to capture. To describe is already to order: to prioritise certain features while consigning others to the margins. As Charles Péguy observed, “il faut toujours dire ce que l’on voit; surtout il faut toujours, ce qui est plus difficile, voir ce que l’on voit” (One must always say what one sees; above all, one must always, which is more difficult, see what one sees).

II. Towards a Comparative Method: reading lists and statistical analysis

It is never easy to explain how a collective – composed of many voices – can appear to think or speak as one. As soon as we ask how such a group “thinks” or “sees”, we are forced to confront the problem of definition: we must first draw the perimeter of the group itself before attributing to it a perspective. And then comes the further step: to make them speak with one voice, to translate a multitude into a single, manageable representation.

This operation can never be perfect. Intelligibility rests on simplification. As George Steiner and even Wittgenstein have stated, no two things are ever perfectly identical; thus no discourse can be entirely collective. The challenge was to ensure that my methodology avoided oversimplification – that I did not achieve clarity at the expense of complexity. What I valued most was heuristics, as opposed to conceptual purity.

My project therefore required a tailored methodology. My idea was to draw from legal anthropology and build a conceptual map that would be both immanent and representative of the groups at hand – British, French, and Canadian constitutional scholars. From this point of view, I saw great value in using reading lists assigned by professors and lecturers to their students. In the space I have left, I will illustrate the first step of this methodology, showing how it can be used to analyse scholarly approaches in general, though I applied it specifically to academic classifications.

Reading lists are not mere bibliographies, though they may take that form. They are a distilled concentration of the very books and articles a lecturer deems essential to understanding what they teach. Not that lecturers necessarily agree with the texts they assign – they may criticise them in class – and even so, the choice to recommend one book rather than another may be shaped by circumstance (economic constraints, publishing, library access). Still, certain books, articles, and authors are recommended more often and therefore more widely read. Their content is thus more broadly diffused. Allowing for statistical analysis – both quantitative and qualitative – can offer a more accurate picture of a living legal culture, beyond mere observation.

When used to compare other legal systems, this methodology reveals what interests constitutional law lecturers, what they overlook, how they establish their priorities, and in what sequence and with what material they pursue them. Comparison thus becomes fruitful. It forces us to confront not only different vocabularies but different sensibilities – what counts as a convincing argument, a relevant precedent, or even a legitimate source of law. It allows the production of conceptual maps, which show to what extent, and in what manner, groups of scholars conceive differently both their expertise and their place within the legal world they seek to describe. Through this work, we can gain a clearer – though never absolute – sense of how a group tends to think and perceive. It thus becomes possible to move upstream and ask how they came to that point.

How has one’s tradition shaped their present dispositions and reflexes? In what follows, I illustrate that inquiry through a specific example: the citation of cases. It exemplifies the mapping itself and shows one way of linking current practices to the traditions from which those intellectual reflexes arose.

III. Topical insights: a concurrence of perspectives

For my study, I solicited dozens of lecturers from the United Kingdom and Canada, and obtained roughly thirty reading lists from each system regarding constitutional law in general for academic years ranging from 2020 to 2023 (due to local particularism, a different methodology was used in France). I obviously used said material in regard to devolution, but the possibilities are almost endless.

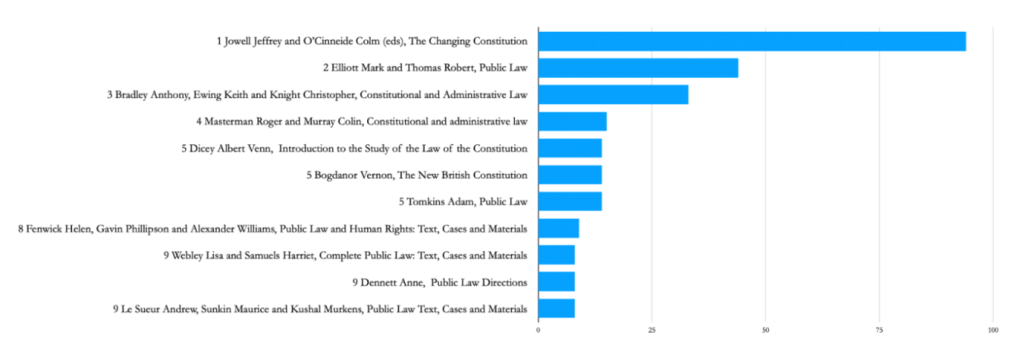

The number of references was staggering: several thousand cases, along with thousands more scholarly works. Once processed, some clear “winners” emerged.

This graph above presents, for example, a ranking of the most frequently cited books across my UK reading lists. Focusing only on the top three – which stand well ahead of the rest – we already gain a strong sense of how constitutional law is generally taught in the United Kingdom. If these three works address the same problems and concepts in the same sequence, we may reasonably infer that they reflect the dominant approach in the UK. From there, comparisons can be drawn with other legal systems, allowing us to assess how constitutional law is taught – and, more importantly, perceived – differently elsewhere. An obvious caveat: we don’t know how these books are used or why they’re popular. Their reading is recommended, but how teachers present them or students interpret them remains unclear. These lists are only indicators: prompts for questions, not conclusions. It is worth bearing in mind that a thermometer is not a diagnosis.

What is striking, however, is how this mass of references can be cross analysed with other data to yield further insights. For instance, one may ask: where was the most widely diffused book published? And how does that compare with the leading textbook in Scotland? Comparing reading lists from Scotland with those from England, Wales, or Northern Ireland allows us to see not only what is taught, but where certain topics receive greater emphasis. Due to the constraints of this post, I will only use one illustration based on case citations in general, leaving aside classifications per se.

An important difference with Canada lies in the way cases are cited. In the UK, relatively few cases attract sustainedcommentary, while many are mentioned only once. This is made clear in my reading lists: only a handful of individual cases are cited more than 4 times across all my 27 lists. In Canada, by contrast, a large number are cited repeatedly across all reading lists. Most UK textbooks or syllabi are also structured around key, often abstract, concepts such as “constitutions”, “sovereignty”, or “the rule of law”. Within any given textbook, even when cases outnumber scholarly works in footnotes, they often serve merely as supportive authority rather than the core of the argument (with little contextualisation or explanation per se). Across our 27 UK lists, only 29% of recommended documents are cases. Some lists barely cite any (Glasgow syllabus: 92 entries, 7 cases). At Exeter, only one decision is cited.

Applying the same method in Canada yields a very different picture: Canadian lists cite substantially more cases (57% of total entries) and structure their textbooks around them. Canadian Constitutional Law, a leading textbook in Canada, for instance, contains very little theory of federalism but extensive commentary on Supreme court decisions – reading it feels like a refined case commentary. That’s never so in any UK textbook I’ve read.

This suggests that case law occupies a far more central place in Canadian legal education, which revolves around cases themselves, whereas in the UK it seems to revolve instead around a few core concepts explained through cases. That is where the notion of tradition becomes useful: I argue that UK academic constitutional law, around Dicey, modelled itself on practice to gain legitimacy. The comparatively low prestige academics once enjoyed justified such focus on practice, but this has faded in reality if not yet in perception throughout the twentieth century – though old representations may linger unevenly across the board. Only when contrasting this with Canada does the shift become clear. In France, le droit constitutionnel was largely the creation of professors who sought to imitate whatever methods appeared most “scientific” and to distance themselves from legal practice entirely.

This is the kind of debate my methodology can open. Each dataset can indeed generate new hypotheses: about the circulation of ideas, the authority of textbooks, or the silent hierarchies that shape academic judgment. I used them for understanding how we think differently of classifications, but the possibilities are many.

Conclusion

It remains daunting to grasp the full extent of how scholars think. What the British constitution is – at least with regard to the devolution of power – depends in large part on what we have been trained to recognise as significant. A Canadian-trained constitutional lawyer will focus on case law and judicial interpretation; a French counterpart will instinctively seek to locate and qualify sovereignty; a British scholar will most likely strive for a precise description rather than a broader classification. And that is the point: three perspectives produce three outcomes, sometimes contradictory yet concurrently valid. It shows there is little “in itself”, and so much more that we bring with our perspectives and our categories, indeed what we think we see.

All my thanks go to Dr. Sophie Turenne for her insightful comments on earlier drafts of this post. All remaining errors are mine.

(Posted by Lucien Carrier)