Introduction

The former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY, 1963–1992; previously known as the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, FPRY, 1945–1963) was a one-party communist state established after World War II. It encompassed the territories of modern-day Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Kosovo. The law of obligations of this state was primarily governed by a federal Law on Obligations (Croatian: Zakon o obveznim odnosima, ZOO; known by different titles in the other official languages of the SFRY). Enacted in 1978, following a decade of preparation, the ZOO was genuinely innovative for its time, standing out for three key reasons: its role within the Yugoslav legal system, its novel content, and its minimal influence from the socialist legal tradition. It was shaped by a scholar who was influenced by the legal achievements from the Interwar period – Professor Mihailo Konstantinović.

An Innovative Piece of Legislation

Foremost, the ZOO was the first comprehensive law governing the law of obligations throughout the entire territory of the SFRY. It brought an end to the prior fragmentation of the Yugoslav legal system in this area of civil law, where multiple different sources were applied across various parts of its territory. Many of these sources, as we shall see below, had remained largely unamended since the 19th century, posing significant challenges for the courts in their application in a vastly different post-World War II political and economic environment.

Furthermore, the ZOO incorporated and built upon the legal concepts developed in foreign case law and scholarship, thus codifying them in the Yugoslav legal system at a time when they were yet to be codified in the legal systems of their origin. For instance, the ZOO introduced a general legal framework for the termination of continuing obligations, explicitly accepting the doctrine of Dauerschuldverhältnisse developed in German and Swiss scholarship. It provided innovative rules for the concept of frustration of contract, detailing the right of a contractual party to obtain modification or termination of contract by the court in the event of an unforeseen change of circumstances. The ZOO rules on precontractual liability closely resembled those later introduced in the Principles of European Contract Law. Although not using the term ‘consumer’, the ZOO introduced specific consumer protection rules, particularly in the regulation of instalment sales. The ZOO also borrowed from then-novel instruments prepared by Unidroit and other international organisations; for instance, it regulated organised and intermediary travel contracts based on the model of the International Convention on Travel Contracts of 1970.

Finally, although the ZOO contained elements characteristic of the prevailing socialist principles of the time, it mostly steered clear of a socialist ideology. The minor influence from the socialist legal tradition is somewhat connected with the fact that SFRY was not a typical communist state. Initially aligned with the Eastern Bloc at the beginning of the Cold War, the SFRY broke away from the Soviet sphere of influence in 1948. Thereafter, it pursued a policy of neutrality, becoming one of the founding members of the Non-Aligned Movement. Embracing its own socialist political philosophy – Titoism, the SFRY transitioned from a command (planned) economy to a form of a market socialism based on socially-owned cooperatives, workers’ self-management, market allocation of capital, and social ownership rather than state ownership.

The Role of a Scholar

However, the ZOO departed from the socialist legal tradition and embraced influences from the Western civil law tradition primarily thanks to the fact that it was largely based on a draft written by Professor Mihailo Konstantinović (1897–1982), which is known as the Sketch for a Code of Obligations and Contracts (‘the Sketch’), published in Obligacije i ugovori: Skica za zakonik o obligacijama i ugovorima (Pravni fakultet u Beogradu 1969). Konstantinović employed a comparative method of study, drawing from diverse foreign legislative models, and blending influences from both the Germanic and the Romanistic legal families.

The legal transfers in the Yugoslav law of obligations discussed in this post occurred post-World War II. Nevertheless, in my opinion, several key factors (discussed below) stemming from the Interwar period paved the way for these legal transfers in an enduring fashion.

At the beginning of the Interwar period, the different nations of the constitutive republics and autonomous provinces of the former SFRY established a common state for the first time in their history (the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, later renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia), informally known as the ‘first’ Yugoslavia. The Interwar period in the first Yugoslavia witnessed an extremely fragmented legal system. The first Yugoslavia encompassed territories previously governed by several distinct legal systems and the pre-existing sources of law were not eliminated upon the establishment of the new state. Consequently, different legal rules coexisted across its territory in each branch and area of law. This fragmentation was particularly pronounced in substantive civil law, manifesting in six regions with six distinct sets of civil law rules, as we shall see below. The Interwar period also witnessed unsuccessful attempts to eliminate conflicts between these regions through a unification process.

In Part I of this post, I will provide a brief overview of the previous political and legal context as it is essential to fully comprehend the intricacies of civil law in the first Yugoslavia during the Interwar period discussed in Part II. During the Interwar period, Professor Konstantinović began his academic career and quickly became one of the leading Yugoslav legal scholars, truly an intellectual giant of his time. His legacy will be explored in Part III. In Part IV, we will dive deeper into Konstantinović’s Sketch and the postwar legal transfers in the Yugoslav law of obligations. Finally, in Part V, I will explain why they remain relevant today in modern-day Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Kosovo – seven states, yet nine jurisdictions, given Bosnia and Herzegovina’s highly decentralised sui generis federal system comprising two autonomous entities and a separate district.

Part I: Civil Law in the Former Yugoslav States Pre-World War I

Since the end of the Late Middle Ages and throughout the Early Modern Age, the region of the former Yugoslavia had been dominated by the Habsburg Monarchy in the north and the Ottoman Empire in the south, with the Republic of Venice incorporating most of the Adriatic coast. At the turn of the 19th century, the French Republic conquered the Republic of Venice and the southwest territories of the Habsburg Monarchy. The 19th century in the region of former Yugoslavia began as the age of empires (with the proclamation of the first French Empire and the Empire of Austria in 1804), coinciding with the age of codification, and continued with violent revolutions and the national awakening. In the 19th century the political and legal history of the former Yugoslav territories became increasingly more complex and this significantly impacted the later turn of events in the 20th century. To bring clarity to the following narrative, I will present it in two sections: the first dealing with the territories within the Austrian Empire, and the second – with those falling under the Ottoman Empire, while the important events within these sections will be presented in a chronological order.

1. Former Yugoslav Territories within the Austrian Empire

During a brief period under the rule of Napoleon, the Code civil of 1804 applied in certain regions of modern-day Slovenia and Croatia, which were then part of the Illyrian Provinces (1809–1814), an autonomous province of the French Empire. After Napoleon’s downfall and the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815), most of modern-day Slovenia and Croatia were part of different kingdoms (Illyria, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia) and other entities (City of Fiume, Croatian and Slavonian Military Frontier), all crown lands of the Empire of Austria. At that time, several Slovenian, Croatian, and Serbian regions were part of the Kingdom of Hungary, itself a crown land of the Empire of Austria. The Austrian General Civil Code of 1811 (Allgemeines bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, ABGB) was introduced to these territories at different points in the 19th century – e.g., the ABGB had been in force in Dalmatia since 1816, while it was introduced to Croatia and Slavonia in 1852 during the Austrian Neoabsolutist era (see e.g., Petrak 107–14).

When Austrian absolutism was abolished (1860), the legislative authority reverted to Croatia and Slavonia, which continued to apply the ABGB. However, it was a Croatian version of ABGB, known as Opći građanski zakonik (OGZ), that became independent from the original Austrian model. OGZ retained the content of ABGB as it stood in 1852 when first introduced to Croatia and Slavonia, and it remained unrevised and unamended (see e.g., Gavella 336–42).

Following the Austro-Hungarian Compromise (1867), which established Austria-Hungary as a real union between the Empire of Austria and the Kingdom of Hungary, the regions comprising modern-day Slovenia and Croatia were divided between the Austrian and Hungarian parts of the dual monarchy, informally known as Cisleithania and Transleithania, respectively. Cisleithania included most of modern-day Slovenia and the Kingdom of Dalmatia. Transleithania consisted of the Kingdom of Hungary, the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, and the free City of Fiume. The Croatian-Hungarian Settlement (1868) affirmed the territorial distinction between Croatia-Slavonia and Hungary and provided for the division of legislative power between the joint Croatian-Hungarian parliament and the national parliaments. Civil law remained within the jurisdiction of the national parliaments, and the OGZ continued to be applied in Croatia-Slavonia. Concurrently, in Dalmatia and other Croatian territories in Cisleithania, as well as in the Slovenian regions, the ABGB was in force with all its subsequent amendments (on ABGB in Slovenia, see e.g., Vlahek and Podobnik 288–90).

Civil law in modern-day Slovenian, Croatian, and Serbian territories that were at that time part of the Kingdom of Hungary was governed by the Corpus iuris Hungarici, a compilation of laws of the lands of the Hungarian crown. The core of the Corpus was the Tripartitum, a codification of customary law that, though never officially enacted, was widely accepted and recognised as a source of law (see e.g., Béli, Petrak, and Žiha 59–76; Nikolić 981–85).

Modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina was a part of the Ottoman Empire until its occupation by Austria-Hungary (1878). The ABGB was applied there alongside the Ottoman Civil Code (Majalla al-Ahkam al-Adliyya) and other sources of Ottoman law (see e. g., Karčić 1030–33; Bećić 71–136).

2. Former Yugoslav Territories within the Ottoman Empire

At the beginning of the 19th century, not only the territories of modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina but also those of modern-day Serbia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Kosovo were under Ottoman rule. In the 19th century both Serbia and Montenegro were first established as principalities (Serbia in 1815; Montenegro in 1852), recognised as independent countries (1878), and later elevated to the status of a kingdom (Serbia in 1882; Montenegro in 1910). Following the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), the Kingdom of Serbia encompassed the modern-day territories of North Macedonia and Kosovo.

The Kingdom of Serbia enacted its Civil Code in 1844 (srpski Građanski zakonik, SGZ), ‘a shortened and somewhat amended version’ of the ABGB (Nikolić 978; see also e.g., Avramović 379–482). In Montenegro, customary law was followed alongside the General Property Code of 1888 (Opšti imovinski zakonik, OIZ), a modern codification prepared by Croatia-born jurist Valtazar Bogišić (1834–1908) which garnered widespread attention from scholars and jurists and was translated in multiple languages (see e.g., Petrak 117–20).

Part II: Civil Law in the First Yugoslavia in the Interwar Period

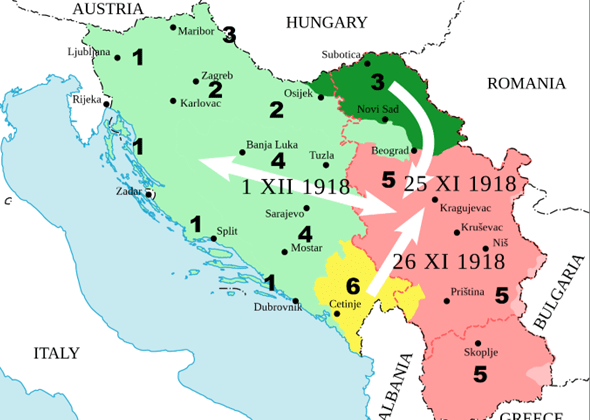

Shortly before the end of World War I and the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, the State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs was proclaimed, encompassing most of the Austro-Hungarian southern regions. In the aftermath of World War I, Montenegro, and several regions previously under Hungarian rule, forming the territory of the modern-day Serbian Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, proclaimed unification with the Kingdom of Serbia. The enlarged Kingdom of Serbia was soon unified with the State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs, and a new state was established on 1 December 1918: the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. When King Alexander I (r. 1921–1934) proclaimed a royal dictatorship in 1929, the integral Yugoslavism, the ideology advocating the idea that South Slavs belonged to a single Yugoslav nation, was officially adopted, and the kingdom was renamed to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Since its inception, the principle of legal continuity applied in the first Yugoslavia, and as a result, the previous legal framework remained in force in the different parts of the newly established Kingdom. Consequently, six different areas with six distinct sets of substantive civil law rules (see e.g., Krešić 153–55; Radovčić 253–56) existed:

- The Slovenian and Dalmatian area, where the ABGB as amended until 1918 was applied.

- The Croatia-Slavonian area, where an unamended and unrevised version of the OGZ was applied.

- Theareas of Međimurje, Prekmurje, and north Vojvodina, where Hungarian customary and judge-made law was applied.

- The Bosnia and Herzegovina area, where the ABGB was applied alongside Ottoman law.

- The Serbian area, where the SGZ was applied.

- The Montenegrin area, where the OIZ was applied.

Each area had its own supreme court; however, a supreme court for the entire Kingdom was not established. To overcome this extreme fragmentation of the legal system, the government initiated a process of unification of civil law in 1919. The OGZ, the Croatian version of the ABGB, was considered to be a common denominator between the six areas, hence it was used as the primary source of inspiration. The result of the unification process was the Preliminary Draft of the Civil Code for the Kingdom of Yugoslavia of 1934 (Predosnova građanskog zakonika za Kraljevinu Jugoslaviju, on which see, particularly, Radovčić 257–301). The Preliminary Draft, like the ABGB, the OGZ, and the SGZ, followed the institutional system that divided private law into persons, things, and actions (personae, res, and actiones). It incorporated elements from the amendments of the ABGB (the three Teilnovellen enacted in 1914–1916), with influences from the Swiss Civil Code (Zivilgesetzbuch, ZGB) and its Law of Obligations (Obligationenrecht, OR), the German Civil Code (Bűrgerliches Gesetzbuch, BGB), as well as drafts of the Czechoslovak and Hungarian civil codes. The Preliminary Draft was met with strong criticism, particularly due to its reliance on the ABGB (see e.g., Orlić, 50–57; Mirković 80–87). It was never enacted: the Kingdom of Yugoslavia ceased to exist without adopting its civil code.

Part III: Professor Mihailo Konstantinović (1897–1982) and His Legacy

Mihailo Konstantinović was born in 1897 in Čačak, Kingdom of Serbia. During World War I, the young Konstantinović served as a clerk in a military hospital in Čačak. In the winter of 1915/16, he retreated with the Serbian army, through Albania, to be evacuated by Allied ships, and then crossed to France, where he finished high school in 1916. He fought in World War I as a volunteer in the French army on the Western Front. He graduated with a degree in law from the Faculty of Law in Lyon in 1920, where he also earned his doctorate in 1923 with a thesis dedicated to Roman law: Le “periculum rei venditae” en droit romain (Bosc frères et Riou 1923). Upon returning to the homeland, he began his academic career in 1924 at the Faculty of Law in Subotica, (then Kingdom of Yugoslavia; now Serbia) and transferred to the Faculty of Law in Belgrade (then capital of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia; now capital of Serbia) in 1935, where he was appointed as tenured professor in 1937 (on Konstantinović’s life and academic career, see e.g., Kršljanin 8–20).

During the Interwar period, Konstantinović opposed the decision to use the OGZ as the starting point for the Preliminary Draft of the Civil Code for the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Drawing inspiration from the purpose of the Code civil as a unifying factor for the French nation, he believed that adopting Austrian civil law would be a ‘national-political mistake’ and that a Yugoslav civil code should be crafted according to the specific needs of the Yugoslav people, serving as ‘a means of creating Yugoslav identity’ (Konstantinović (1933) 388). He advocated for the Montenegrin OIZ as a model for a Yugoslav civil code, asserting that the OIZ was more advanced than the ABGB and better suited to the needs of the Yugoslav people (Konstantinović (1933), 391–92). This was not surprising since he admired Bogišić and his codification work (see e.g., Konstantinović (1938) 422–24).

In addition to his academic work during the Interwar period, Konstantinović was highly engaged in the legal profession and he was politically active. In 1939, he joined the government, first as a minister without portfolio, and later as the Minister of Justice. He resigned from this position in March 1941, opposing Yugoslavia’s accession to the Tripartite Pact. Following the Axis powers’ invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, Konstantinović fled to Egypt, spent most of World War II in exile in different countries, and returned from London to Belgrade in February 1945. He served as the head of the Department of Civil Law at the Faculty of Law in Belgrade for two decades until his retirement. Additionally, he was the Faculty’s Dean for three terms (1947–1948, 1951–1953, and 1959–1960). He initiated the establishment of a new faculty journal in 1953, Anali Pravnog fakulteta u Beogradu (The Annals of the Faculty of Law in Belgrade – Belgrade Law Review), and served as its chief editor from its inception until 1960. He was one of the main proponents of establishing the Foreign Trade Arbitration Tribunal at the Yugoslav Chamber of Commerce and served as its first president (1947–1974) (see e.g., Jovanović 159).

Following World War II, the Act on the Immediate Nullification of Laws and Regulations Adopted Before 6 April 1941 and During the Enemy Occupation (1946) was the starting point that shaped the course of private law in the FPRY. This act nullified all prior codes and legislation used in the pre-World War II six areas, stripping them of their status as direct sources of law. However, it allowed for their limited application as auxiliary sources of law, provided that a particular legal provision from these former codes and laws had not been superseded by newer Yugoslav legislation and was not in conflict with the Constitution of the FPRY.

Konstantinović was the president of the commission for drafting the Constitution of the FPRY (1946) and the chief architect of many important federal pieces of legislation in the area of private law. These include the Principal Law on Marriage (1946), Principal Law on Adoption (1947), Principal Law on Parent-Child Relationship (1947), Principal Law on Legal Guardianship (1947), Law on the Prescription of Claims (1953), and the Law on Inheritance (1955).

The Law on the Prescription of Claims, modeled by Konstantinović on provisions of the Swiss OR, was the sole relevant federal piece of legislation enacted in the area of the law of obligations during the FPRY era. Swiss law also served as a model for Konstantinović when preparing the Draft of the Law on the Compensation of Damages (1951), but it was never enacted.

In this period, the State Arbitration Tribunal, the supreme authority for commercial disputes at the time (1946–1954), a precursor of the Supreme Commercial Court of the FPRY, released a significant source of commercial contract law, designed specifically to fill an existing legal vacuum. Known as the General Usages for the Sale of Goods (1954), these rules, despite their title, were not a codification of trade customs but instead a creation by a group of experts led by Professor Aleksandar Goldštajn (1912–2010). They were applied as if they were non-mandatory provisions of a law. They were to be applied when the contracting parties agreed to their application. Additionally, they provided for a presumption that the parties had agreed to their application where, in the case of a dispute, the jurisdiction of a commercial court was prescribed or agreed upon. These rules were also not a codification of Yugoslav case law; rather, they were developed by borrowing rules from various foreign jurisdictions. They incorporated rules largely borrowed from the Swiss OR and the German Commercial Code of 1897 (Handelsgesetzbuch, HGB), and included transfers from other jurisdictions (see e.g., Goldštajn 355–56). Notably, the rules on the termination of a contract in the event of changed circumstances were influenced by the Italian Codice Civile of 1942 (see e.g., Nikšić 590, 607).

In 1960, a group of government officials entrusted Konstantinović with the task of preparing a preliminary draft of the codification of the law of obligations. His work on his magnum opus, the Sketch, began then and culminated with its publication in 1969. However, the Sketch was not published as an official draft but rather as Konstantinović’s personal proposal for the codification.

Part IV: The Sketch for a Code of Obligations and Contracts (1969) and the Yugoslav Law on Obligations (1978)

In his introduction to the Sketch (Konstantinović (1969) 7–8), Konstantinović explained that ‘the basic idea in composing this sketch was to find solutions […] that would be fair and best suited to the needs of practical life. […] Therefore, the main part of material was taken from our legal life, especially from our case law. […] [I]n foreign legislation, some issues in this area have been resolved in a way that better meets the needs of practical life than our old legal rules. That is why this sketch includes a greater number of borrowings from foreign legislation. Some of them are taken from there in the form they have in the original, whenever it seemed that a clear and precise formula was found there. On that occasion, it is necessary to emphasise that the goal was not to achieve originality in every aspect and at any cost. […] Through the same lens through which foreign legislation was observed […] various legal theories in foreign law and legal scholarship in general were examined: their conclusions were translated into the texts of the sketch whenever it seemed that they corresponded to the needs of our legal system.’

The Yugoslav General Usages for the Sale of Goods of 1954 and case law arising from their application were among the sources used in the preparation of the Sketch (see e.g., Slijepčević 22; Tot 9–10). Unfortunately, Konstantinović never explicitly detailed the foreign sources considered when drafting the Sketch. The only sources he explicitly mentioned in his introduction to the Sketch (Konstantinović (1969) 7–8) were the 1964 Hague Conventions relating to a Uniform Law on the International Sale of Goods (ULIS) and to a Uniform Law on the Formation of Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (ULFC). Konstantinović generalised their provisions and incorporated them into the Sketch, expanding their application to all types of contracts. The provisions of the Sketch show a significant influence of the ULIS on the regulation of contract termination due to non-performance and on the regulation of the contractual liability for damages, while the influence of the ULFC is primarily visible in the provisions on the formation of contract (Tot 13).

Identifying the precise models for individual provisions within the Sketch is challenging, if not a Sisyphean task. Many provisions in the Sketch amalgamate elements from several different legal systems and, given the historical influence of European legal systems on one another, pinpointing the sources for specific solutions in the Sketch can be difficult. Nevertheless, concrete examples of identified comparative legal influences on the Sketch can be offered (for a detailed overview of the comparative influences on the Sketch, see Tot 11–20).

Noteworthy elements were borrowed from Swiss law. In the law of delict (tort), this influence is especially evident in the provisions regarding compensation for non-pecuniary damage and strict liability for dangerous objects and activities. Swiss influences are also evident in the regulation of assignment of claims, impossibility of performance, instalment sales, and in the focus of the Sketch on contract (Vertrag) rather than on a broader concept of a legal transaction (Rechtsgeschäft), the latter approach being characteristic of the German BGB.

Swiss and German law played a pivotal role in shaping general contract law, as well as the regulation of specific contracts and unjustified enrichment in the ZOO. The influence of the German BGB can be discerned in various areas, including provisions concerning the conversion of invalid contracts, the principle of simultaneous performance of reciprocal obligations and the exception of non adimpleti contractus, usurious contracts, contractual penalties, plurality of debtors and creditors, assumption of debt, loan agreements, usufructuary leases, and numerous others. The Sketch incorporated the German doctrine of continuing obligations and introduced a general framework for the termination of continuing obligations, influenced by both German and Swiss legal scholarship and case law.

The Sketch was significantly impacted by legal systems belonging to the Romanistic legal family, especially by French and, to some extent, Italian law. One notable influence of French law was the incorporation of la cause as a condition for the validity of contract. Additional prominent French influences on contract law can be seen in the regulation of subrogation and contractual liability for damages. The Sketch’s law of delict (tort) was primarily shaped by French law, introducing concepts such as the general principle of fault as the basis for non-contractual liability for damages. In this framework, objective wrongfulness is not an independent prerequisite for non-contractual liability but is integrated within the broader concept of fault.

The influence of the Italian Codice Civile is distinctly present in the areas of contract interpretation, the transfer of a contract, and the rescission of a contract in the event of changed circumstances.

Minor Austrian influences are also visible in the Sketch, particularly in the regulation of the concept of laesio enormis and the prohibition of ultra alterum tantum (interest exceeding the principal debt amount).

The selection of comparative templates for the Sketch appears to be profoundly impacted by Konstantinović’s life path and his scholarly views which developed during the Interwar period. Considering his aspiration to prepare a modern code that would meet the needs of Yugoslav legal practice, the reasons for relying on the Swiss OR and the Italian Codice Civile in the preparation of the Sketch are clear. A significantly smaller influence of Austrian law on the Sketch compared to other legal sources is understandable, given his opposition to Austrian law as a model for a Yugoslav civil code during the Interwar period. The influence of French Code civil can be attributed to Konstantinović’s background and education in France in the Interwar period, and his lifelong admiration for French law.

There is a seemingly overlooked legal source, stemming from the Interwar period, that likely aided Konstantinović in drafting the Sketch, which could provide insights into the influence of French and Italian law on the Sketch. This is the Franco-Italian Draft Code of Obligations and Contracts from 1927, which was never enacted in France and Italy but left its mark on the regulation of the law of obligations in countries such as Poland, Albania, and Egypt (for Poland, see e.g., Kryla-Cudna in a previous post in this series). Surprisingly, this Draft Code has received no attention in former Yugoslav scholarship.

However, recently, there have been attempts to demonstrate its influence on the Sketch (see Tot 20–24). A comparison of the structure of the Sketch, the Franco-Italian Draft, and other available comparative sources from Konstantinović’s time showed that the Sketch, in its structure, although not identical, is closest to the Franco-Italian Draft. The likely influence of the Franco-Italian Draft on the Sketch is indicated by the similarity in their titles. Characteristics that are often portrayed as a distinctive influence of Swiss law on the Sketch (the monistic concept of obligations, the focus on contracts rather than legal transactions in general, the integration of regulation on non-contractual obligations within the general part of the law of obligations, as well as a linguistic style where each paragraph consists of only one sentence are also distinctive features of the Franco-Italian Draft.

While further and extensive research needs to be yet undertaken to pinpoint the exact borrowings from the Franco-Italian Draft in the Sketch, it is certain that Konstantinović was aware of the existence of the Franco-Italian Draft and its content. In some of his earlier works, he referenced the provisions of the Draft (e.g., Konstantinović (1952) 509; Konstantinović (1953) 211). Therefore, it is unlikely that he would not have borrowed from it when preparing the Sketch.

Following the publication of the Sketch, Konstantinović was not involved in the drafting of the Yugoslav ZOO of 1978. It is worth noting that when Konstantinović published the Sketch, he envisioned it as part of a future Yugoslav civil code; thus, he referenced ‘code’ in the title of the Sketch rather than ‘a law’. At that time, the Parliament of the SFRY formed a special Civil Code Committee, which included a Subcommittee on the Preparation of the Part of a Civil Code Related to Obligations. The general consensus was that the work on a Yugoslav civil code would begin with the codification of the law of obligations, considering the Sketch as a solid basis for this endeavour.

The constitutional foundation for a federal civil code was laid in the 1963 Constitution of the SFRY, which placed ‘comprehensive laws’ (‘potpuni zakoni‘) related to the civil law within federal jurisdiction. However, this foundation was revoked in 1971 through a constitutional amendment, which stipulated that only ‘basic’ laws (‘osnovni zakoni‘) in the area of civil law fell under federal jurisdiction. Additionally, the amendment limited the federation to regulating only the obligations in the field of trade in goods and services. The 1974 Constitution of the SFRY also outlined a similar division of legislative powers between the federal Yugoslav parliament and republic parliaments. Since the federation was no longer authorised to enact ‘comprehensive laws’, the plan to create a Yugoslav civil code was abandoned. Nevertheless, work on codifying specific areas of civil law persisted, leading to the enactment of several federal laws, including the ZOO, i.e. the Law on Obligations of 1978.

The committees working on the ZOO used the Sketch as the basis. However, during the drafting of the ZOO, some concessions were made to align the law with socialist principles. Notably, freedom of contract was restricted by the ‘morale of the socialist self-management society’. Additionally, the ZOO significantly diverged from the Sketch with regard to specific rules. For instance, while the Sketch adopted the concept of a fundamental breach of contract from the ULIS, the ZOO did not introduce this concept (see e.g., Možina 151–55). The Yugoslav legislature also drew inspiration from other socialist legal systems, resulting in the incorporation of several rules from the second Soviet Civil Code (1964), the Czechoslovak International Trade Code (1963), and the International Commercial Contracts Act of the German Democratic Republic (1976). Nonetheless, the majority of the Sketch’s provisions were incorporated into the ZOO without changes (on the drafting of the ZOO, the foreign influences on the ZOO, and deviations from the Sketch, see Tot 24–55).

Part V: Concluding Remarks: the Yugoslav Law on Obligations Today

A question that one might reasonably ask needs to be answered: why is it necessary to investigate legal transfers in the legislation of a state that no longer exists today?

Following the violent breakup of the SFRY, during the reforms aimed at facilitating the transition of the political and economic system in each of the former Yugoslav states, the ZOO – formerly federal legislation – continued to be applied as a national legislation – in the seven states which emerged from the former SFRY. It also significantly impacted later reforms of the law of obligations in these states (for a concise overview, see e.g., Slakoper and Tot 13–22). Given that the socialist influence on the Yugoslav ZOO was minimal, it proved relatively straightforward to adapt and adopt it as national legislation in the new democracies.

In Slovenia, the Yugoslav ZOO was supplanted by the new Code of Obligations in 2001, yet the new code retained the structure and most of the substance of the Yugoslav ZOO: it is described as more a formal than a substantial reform of the law of obligations (see e.g., Možina and Vlahek, para 36). Moreover, the Yugoslav ZOO in its Slovene version is still partly in force since the new code had not repealed its provisions on banking contracts. Similarly, in Croatia, the Yugoslav ZOO was first adopted as Croatian legislation and then replaced in 2005 with the new Law on Obligations, which borrowed almost the entire text of the Yugoslav ZOO, but restructured and adjusted it to comply with Croatian legal terminology. In each of the three constitutive parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Yugoslav ZOO is still in force, albeit in three different versions: in the Brčko District it is applied in its original version without subsequent amendments, while in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republic of Srpska it is applied as amended in these two entities. In Serbia, the Yugoslav ZOO is still in effect with its subsequent amendments, and it was also used as the base for regulating the law of obligations in the not-yet-enacted 2015 Draft Civil Code of the Republic of Serbia. New pieces of legislation governing the law of obligations were also adopted in North Macedonia in 2001, in Montenegro – in 2008, and in Kosovo – in 2012, with each of them taking over the structure and most of the substance from the Yugoslav ZOO. The law of obligations in the recent draft civil codes in these three countries was also heavily impacted by the Yugoslav ZOO.

Hence, with the Sketch as its backbone, the Yugoslav ZOO lives on as the common core of the law of obligations in the former Yugoslav states. The continuing reliance on the Yugoslav ZOO means that when discussing legal transfers from various jurisdictions within the law of obligations in modern-day Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Kosovo, exploring Konstantinović’s Sketch and drafting of the Yugoslav ZOO is imperative.

Posted by Dr Ivan Tot, Assistant Professor and Head of the Department of Business Law at the University of Zagreb, Faculty of Economics and Business, Croatia (itot[at]net.efzg.hr)

This piece belongs to Season 2 of the “Cross-jurisdictional dialogues in the Interwar period” series dedicated to less-known legal transfers which have had a palpable impact on the advancement of the law. The Interwar period was a time of disillusionment with well-established paradigms and legislative models, but also a time of hope in which comparative dialogue and exchange of ideas between jurisdictions thrived. The series is edited by Prof Yseult Marique (Essex University) and Dr Radosveta Vassileva (Middlesex University). To access the other pieces from this series, either select the ‘Interwar Dialogue’ category or click on the #Series_Interwar_Dialogue tag on the BACL Blog.

Suggested citation: I Tot, ‘The Yugoslav Obligations Act of 1978 and the Legacy of Professor Mihailo Konstantinović (1897–1982): The Influence of the Interwar Period on Post-WWII Legal Transfers’, BACL Blog, available at https://british-association-comparative-law.org/2024/03/08/the-yugoslav-law-on-obligations-of-1978-and-the-legacy-of-professor-mihailo-konstantinovic-1897-1982-the-influence-of-the-interwar-period-on-postwar-legal-transfers-by-ivan-tot/

Picture credits

‘Creation of Yugoslavia – map with merger dates’ (Wikimedia Commons, 3 November 2023). This file is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication. Indications of the six areas added by Ivan Tot.

‘Mihailo Konstantinović‘ (Wikipedia, 3 November 2023)

‘Skica’ (Antikvarijat Zlatarevo Zlato, 3 November 2023)

Bibliography

Avramović S, ‘The Serbian Civil Code of 1844’, in Simon T (ed), Konflikt und Koexistenz: Die Rechtsordnungen Südosteuropas im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, vol. 2 (Klostermann 2017), 379–482.

Bećić M, ‘Das Privatrecht in Bosnien-Herzegowina (1878–1918)’ in Simon T (ed), Konflikt und Koexistenz: Die Rechtsordnungen Südosteuropas im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, vol. 2 (Klostermann 2017), 71–136.

Béli G, Petrak M, and Žiha N, ‘Corpus Iuris Civilis i Corpus Iuris Hungarici: Utjecaj rimske pravne tradicije na ugarsko-hrvatsko pravo’ in Župan M and Vinković M (eds), Suvremeni pravni izazovi: EU – Mađarska – Hrvatska (Pravni fakultet Sveučilišta Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku and Pravni fakultet Sveučilišta u Pečuhu 2012), 59–76.

Gavella N, ‘Građansko pravo u Hrvatskoj i kontinentalnoeuropski pravni krug – u povodu 140. godišnjice stupanja na snagu OGZ u Hrvatskoj’ (1993) 43 Zbornik Pravnog fakulteta u Zagrebu 335.

Goldštajn A, ‘Lex mercatoria i domaće trgovačko pravo: U povodu četrdesetogodišnjice Općih uzanca za promet robom’ (1994) 44 Zbornik Pravnog fakulteta u Zagrebu 363.

Jovanović M, ‘Doprinos Mihaila Konstantinovića modernizaciji jugoslovenske privrede – stvaranje Spoljnotrgovinske arbitraže’ (2022) 70 (5) Anali Pravnog fakulteta u Beogradu 159.

Karčić F, ‘Opšti građanski zakonik u Bosni i Hercegovini: kodifikacija kao sredstvo transformacije pravnog sistema’ (2013) 63 Zbornik Pravnog fakulteta u Zagrebu 1027.

Konstantinović M, ‘Jugoslavenski građanski zakonik (Austrijski ili Crnogorski zakonik?)’ (1933) 1 (2–3) Pravni zbornik 74 [reprinted in: (1982) 30 Anali Pravnog fakulteta u Beogradu 384].

Konstantinović M, ‘Ideje Valtazara Bogišića o narodnom i zakonskom pravu’ (1938) 1 Sociološki pregled 272 [reprinted in: (1982) 30 Anali Pravnog fakulteta u Beogradu 422].

Konstantinović M, ‘Osnov odgovornosti za prouzrokovanu štetu’ (1952) 2 Arhiv za pravne i društvene nauke 1153 [reprinted in: (1982) 30 Anali Pravnog fakulteta u Beogradu 507].

Konstantinović M, ‘Priroda ugovorne kazne – smanjenje od strane suda’ (1953) 1 Anali Pravnog fakulteta u Beogradu 209.

Konstantinović M, Obligacije i ugovori: Skica za zakonik o obligacijama i ugovorima (Pravni fakultet u Beogradu 1969).

Krešić M, ‘Yugoslav private law between the two World Wars’ in Giaro T (ed), Modernisierung durch Transfer zwischen den Weltkriegen (Klostermann 2007), 151–168.

Kršljanin N, ‘Mihailo Konstantinović (1897–1982): pravnik koji je obeležio jednu epohu’ (2022) 70 (5) Anali Pravnog fakulteta u Beogradu 7.

Kryla-Cudna K, ‘Unifying European Private Law in the Interwar Period: The Case of the Franco-Italian Draft Code of Obligations and the Polish Code of Obligations’ (BACL.blog, 3 February 2023).

Mirković ZS, ‘Mihailo Konstantinović o radu na građanskom zakoniku u međuratnoj Jugoslaviji’ (2022) (70) 5 Anali Pravnog fakulteta u Beogradu 83.

Možina D, ‘Breach of Contract and Remedies in the Yugoslav Obligations Act: 40 Years Later’ [2020] Zeitschrift für Europäisches Privatrecht 134.

Možina D and Vlahek A, Contract Law in Slovenia (Wolters Kluwer 2019).

Nikolić D, ‘Legal Culture and Legal Transplants: Serbian Report’ in Sánchez Cordero JA (ed), Legal Culture and Legal Transplants / La culture juridique et l’acculturation du droit, vol. 2 (International Academy of Comparative Law, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, and Centro Mexicano de Derecho Uniforme 2012), 957–1001.

Nikšić S, ‘Temeljna obilježja instituta izmjene ili raskida ugovora zbog promijenjenih okolnosti’ in Gliha I and others (eds), Liber amicorum Nikola Gavella: Građansko pravo u razvoju: Zbornik radova u čast 70. rođendana profesora emeritusa Nikole Gavelle (Pravni fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu 2007), 563–606.

Orlić MV, ‘Mihailo Konstantinović i preuređenje građanskog prava u srpskom i ranijem jugoslovenskom pravu’ (2022) 70 (5) Anali Pravnog fakulteta u Beogradu 43.

Petrak M, ‘Kodificiranje građanskog prava u jugoistočnoj Europi’ in Tot I and Slakoper Z (eds), Hrvatsko obvezno pravo u poredbenopravnom kontekstu: Petnaest godina Zakona o obveznim odnosima (Ekonomski fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu 2022), 101–146.

Radovčić V, ‘Pokušaj kodifikacije građanskog prava u staroj Jugoslaviji (“Predosnova građanskog zakonika za Kraljevinu Jugoslaviju”)’ (1975) 7 (1) Radovi Instituta za hrvatsku povijest 249.

Slijepčević RM, ‘Nastanak i karakteristična obeležja koncepcije Zakona o obligacionim odnosima’ in Vukadinović RD (ed), Trideset godina Zakona o obligacionim odnosima – de lege lata i de lege ferenda (Zbornik radova) (Pravni fakultet Univerziteta u Kragujevcu 2008), 19–28.

Slakoper Z and Tot I, ‘Recodification and recent developments in the law of obligations in Central and Southeast Europe’ in Slakoper Z and Tot I (eds), The Law of Obligations in Central and Southeast Europe: Recodification and Recent Developments (Routledge 2021), 1–29.

Tot I, ‘Poredbenopravni utjecaji na Zakon o obveznim odnosima’ in Tot I and Slakoper Z (eds), Hrvatsko obvezno pravo u poredbenopravnom kontekstu: Petnaest godina Zakona o obveznim odnosima (Ekonomski fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu 2022), 3–99.

Vlahek A and Podobnik K, ‘Slovenia: Chronology of Development of Private Law in Slovenia’ in Lavický P, Hurdík J, and others, Private Law Reform (Masaryk University 2014), 283–329.

2 Comments

Comments are closed.