Introduction

The emergence of the modern Republic of Turkey (or Türkiye as some Turks prefer) is a compelling chapter in the rapid transformation of formal legal structures. In the mid-1920s, Turkey underwent a series of reforms aimed at modernisation, seeking to shed the historical epithet of the “sick man of Europe”. While reforms, such as the abolition of the caliphate, the banishment of the Ottoman family, and the imposition of laws against traditional headgear, garnered attention, a central aspect of this transformation involved the modernisation and reform of the legal system.

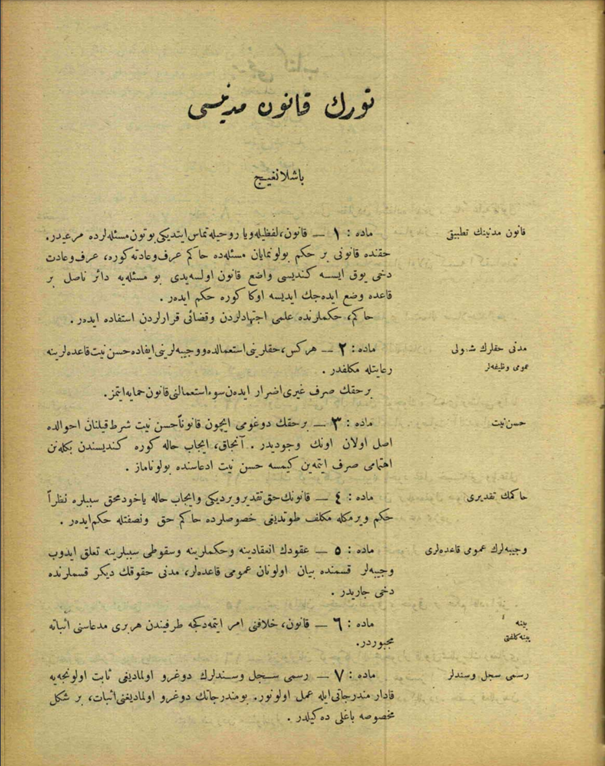

In 1926, Turkey took a bold step by adopting the Swiss Civil Code and the Swiss Code of Obligations, an act that significantly influenced the country’s legal landscape and garnered interest among legal scholars at that time (see e.g. L. Ostrorog, The Angora Reform, Warwick, 1927).

The adoption of Swiss legislation in Turkey is an exemplary case of legal transplants, as noted by legal scholars (A. Watson, Legal Transplants. Ann Approach to Comparative Law, 1993, pp. 114-116; C. Hamson, “The Istanbul Conference”, International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 1956, vol. 26, pp. 26-39). The Turkish case, viewed through the lens of Watson’s conception of legal transplants (see W. Ewald, “Comparative Jurisprudence (II): The Logic of Legal Transplants”, The American Journal of Comparative Law, vol. 43, no. 4, 1995, pp. 489–510) challenges the traditional notion that law mirrors socio-economic factors. The latter is traditionally linked to the writings of Montesquieu and Savigny. Their views have been referred to as the “mirror theories of law”. (see Ewald, op. cit., p. 490, 492). The intriguing choice of the Swiss legal system signalled a radical departure from Turkey’s Ottoman legacy.

Contextualising the Legal Reforms

To appreciate the transplantation of the Swiss Civil Code, it is crucial to contextualise the legal reforms in Turkey leading up to this pivotal moment. The late Ottoman Empire had experienced previous attempts at legal modernisation during the Tanzimat reforms of the mid-19th century. While these reforms aimed at aligning the legal system with European standards, progress was partial. In particular, they did not result in creating a unitary legal system: many groups of the Empire’s population were subject to legal orders of religious communities, known as millets, which they belonged to (I wrote about it for Polish readers here: M. Tutaj, “Between mixed jurisdictions and legal pluralism – case study of the late Ottoman Empire” (in Polish), Przegląd Prawniczy Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2020, vol. 1, pp. 136–154).

From a private law perspective, there are two events worth attention. Firstly, in the Tanzimat period, some pieces of legislation and solutions borrowed from abroad were implemented – e.g. the commercial code of 1840 (based on the French one).

Secondly, the Mecelle (Majalla), sometimes called Code Civil Ottoman, came into force in 1877. The Mecelle sought to blend traditional and modern legal principles of private law, mirroring Islamic legal traditions, particularly of the dominant Hanafi school in Turkey. It consisted of sixteen books combining material (e.g. on sale – book I), procedural (e.g. evidence – book XV) and organisational (the organisation of the courts – book XVI) matters, but it was primarily focused on the law of obligations. The plans to reform the other branches of civil law, such as family law, were unfulfilled. It is interesting that the Mecelle survived longer than the Ottoman Empire itself, as in some parts of the Middle East (e.g. Iraq, Israel, etc.) it was applicable in the post-WWII period.

From the wider perspective of legal theory, the Tanzimat reforms were important for two reasons. They seeded the idea of modernisation via borrowings from the West in the minds of Ottoman modernists. In addition, the reforms paved the path for lawmaking in the areas formerly covered by sharia law. Historically, compared to other Muslim rulers, the Ottoman sultans’ rights to adopt laws were more widely accepted by society and jurists. However, the enactment of the Mecelle was the next step forward and it exemplifies a shift in paradigm. The state codified and approved some sharia rules that had been subject to the exclusive competence of Islamic jurists earlier and, therefore, to a significant extent, had been free from influence by the sultans (on the tensions related to lawmaking in Islamic law, see e.g. K. Vikor, Between God and the Sultan: A History of Islamic Law, Oxford 2005).

This may be one of the reasons why the Ottoman government was able to enact the Family Code in 1917, during WWI. This ephemeral, yet interesting piece of legislation is worth a separate discussion beyond the scope of this piece. However, it is important to note that the mere act of codification of family law, the branch of law which is the most sensitive to a given religious community, was a harbinger of change.

The Circumstances of Transplanting the Swiss Civil Code

The Ottoman Empire was on the losing side in WWI; however, it won the war with Greece, which is known as the War of Independence in Turkish historiography. The latter allowed to overturn the Sevres Treaty and replace it with the Lausanne Treaty, thus avoiding the harsh partitioning of the Ottoman Empire envisaged in the Sevres Treaty. It also gave the military chief and WWI hero who was particularly famous for his role in the battle of Gallipoli in 1915-1916, Mustafa Kemal Pasha (later known as Atatürk, which means the “Father of the Turks”), the mandate and power to carry out a radical change in Turkish history. By the early 1920s, under his leadership, Turkey embarked on an ambitious programme of revolutionary modernisation. The revolution was far reaching and pushed boundaries of the legal and political system as well as social norms further and further. The fate of civil law “codification” is a good example.

The initial idea of the reform was to use the 1917 Family Code as a cornerstone on which to build the new Turkish-style civil code. However, as the reforms unfolded, the evolutionary approach seemed to lose the support of decision-makers and they decided to follow a more revolutionary path. One of the factors behind it could be Mustafa Kemal’s dislike of the old legal elite. The idea of a truly Turkish code created organically by legal scholars was abandoned in 1924 and the new codification committee decided to adopt a foreign-inspired civil code. The new Minister of Justice (Mahmut Bozkurt) claimed that there was no reason for drafting a new code, which could take a long time, as not only there were civil codes available to borrow, but also there was abundant scholarly literature dedicated to them (Y. Atamer, “Rezeption und Weiterentwicklung des schweizerischen Zivilgesetzbuches in der Türkei”, Rabels Zeitschrift für ausländisches und internationales Privatrecht 2008, vol. 72/4, p. 729). Probably, the additional reason for choosing to adopt foreign law was to comply with the requirements of the Treaty of Lausanne, as it obliged Turkey to implement laws that treat all citizens equally. There could be no doubt that the private law borrowed from the West met this criterion.

Switzerland, a neutral country with a well-established legal tradition, was seen as a model for the type of legal system that Turkey wanted to adopt. The Swiss Civil Code, with its emphasis on individual rights, equality before the law and a clear and comprehensive legal framework, appealed to Turkish leaders. This was reflected in Mahmut Bozkurt’s speech in which he described the Swiss Civil Code as the newest, the best and the most people-oriented civil code (available here in Turkish: https://hukukbook.com/743-sayili-turk-kanun-u-medenisi-gerekcesi/). Others might say that the real reason was that many Turkish legal elites had previously studied in Switzerland, as it was a popular study destination for the sons of the Ottoman upper class in the Tanzimat and post-Tanzimat eras. In principle, the Ottoman elites studied French as a foreign language. Bozkurt himself defended his doctoral thesis in Fribourg and was also active in Lausanne-based Turkish circles (see more on Bozkurt: H. Kieser, Mahmut Bozkurt und die „Revolution des Rechts” in der jungen Republik Türkei. In: H. Kieser, A. Meier, W. Stoffel (Eds.), Revolution Islamischen Rechts. Das Schweizerische ZGB in Der Türkei, Zürich 2008, pp. 49–58). In my opinion, we will never know the real reasons why the Swiss civil law was chosen. Many factors may explain such a choice (e.g. simpler language than in the German Civil Code, no political concerns about Switzerland, influence of Swiss advisors e.g. prof. Georges Sauser-Hall advised the Turkish government on the reforms). In 1926, Turkey officially adopted the Swiss Civil Code and the Swiss Code of Obligations, marking a radical departure from its Ottoman past.

The Codes

The Turkish codes are often described as translations of the Swiss codes. In fact, the Turkish versions were based on the translation of the French version of the Swiss Civil Code and Code of Obligations.

However, there were some differences between the Turkish codes and their Swiss counterparts. Some of them were due to the different organisational status of Turkey. The Swiss codes refer in some matters to cantonal regulations. Turkey was and is a much more centralised country. Moreover, there were also differences due to other factors – for instance: i) the default marital property regime was a separation of property of spouses (instead of a community of property as under the Swiss Civil Code of 1907); ii) in case of non-testamentary succession, the entitlement of the spouse was slightly lower than in Switzerland; iii) the age of majority was lowered.

On this basis, some authors (see for example, R. Miller, “The Ottoman and Islamic Substratum of Turkey’s Swiss Civil Code”, Journal of Islamic Studies 2002, vol. 11/3 pp. 335-361) try to unmask the Turkish codes and reveal the hidden traditional and Islamic background embedded in the codes. However, I am rather sceptical about such bold theses. Indeed, some changes were related to local factors, and Turkish scholars admit this (for instance, the different default regime of marital property), but in my opinion the extent of the differences and the materiality of the changes justify treating them as minor adjustments. These adjustments do not challenge the revolutionary nature of the reform, particularly in the area of marriage, which is now a civil union, rather than a religious ceremony.

Moreover, in the 1930s there were other changes that minimised the influence of Islam on Turkish civil law. For example, in the Code of Obligations, Sunday replaced Friday (the day of prayer in Islam) as a day off for apprentices and as a day to extend the deadline for fulfilling obligations (see the 1935 reform).

Further Fate

There were two major open questions for the Turkish experiment with adopting foreign civil law: i) would the socio-economic factors affect the shape of the Turkish codes?; and ii) if not, would it still mirror the letter and spirit of its Swiss counterpart?

These problems were partly addressed during a special conference held in Istanbul (see the report on this conference: C. Hamson, op.cit. pp. 26–39). There were differing opinions (the papers are collected in Social Science Bulletin, 1957, vol. 9) as to whether the law actually affected the lives of ordinary people, especially outside the big cities. However, the contributors agreed that there was no room for changing the path of modernisation. They also noted that Turkish scholars and judges were very attentive in observing the legislative developments of the Swiss Civil Code and the way in which its legal rules were applied in Switzerland (some examples – I. Postacioglu, The Technique of Reception of a Foreign Code of Law, “Social Science Bulletin”, 1957, vol. 9, pp. 54–60, Y. Atamer, op. cit., pp. 723–754).

In the post-WWII period, both the Turkish Code of Obligations and the Civil Code underwent some changes (for instance, in the law of succession, illegitimate children were given the same rights as legitimate children), and some of them can be considered to have been influenced in some way by local customs (for instance, by broadening the scope of persons entitled to compensation for gifts that were inappropriate because of the end of the betrothal). Nevertheless, they were neither very extensive, nor did they change the secular nature of the codes.

Draft reforms of the Civil Code often referred to solutions adopted in Switzerland, although the Turkish legislature did not simply mirror Swiss developments. Turkish case law also tended at times to deviate from the solutions applied in Switzerland, particularly in the area of recognising the acquisition of real estate on land that is not recorded in the land register. Bear in mind that the informal trade in agricultural land was a major issue in Turkey.

Nevertheless, the relationship between Swiss and Turkish civil law was so close that some authors used to speak of a “Swiss-Turkish” law (E. Örücü, “A Synthetic and Hyphenated Legal System: The Turkish Experience”, The Journal of Comparative Law, 2006, vol. 2/1, pp. 261–281). Academics from Switzerland and Turkey often meet and discuss the intermingling of these legal systems, although in reality it is almost always Switzerland that influences Turkey, not the other way round (see, for example, R. Büren (ed.), Rezeption und Autonomie : 80 Jahre türkisches ZGB : Journées turco-suisses, Bern 2006).

The Turkish academic tradition during WWII was influenced by academics from Germany and Switzerland. The influence of Professors Ernst Hirsch and Andreas Schwarz was particularly important. They both had a significant influence on the training of a generation of Turkish legal scholars. Moreover, Schwarzwas an established civil law expert , whereas Hirsch significantly contributed to developing Turkish commercial law. (read more about them and other jurists here: https://forhistiur.net/2007-07-reisman-andic/).

Conclusion

The 21st century brought the legislative change that is both extensive and – paradoxically, at the same time – not as material as one could suppose.

Namely, Turkey promulgated a new Civil Code (2002) and a new Code of Obligations (2011). One might say that this was the perfect opportunity to depart from the “Swiss past” and create a brand new code. But this would not be correct. The main reason for the adoption of the new codes was to modernise the language, which after 80 years was almost unintelligible to anyone but lawyers. In many areas, the new law mirrors the old one. In some respects, it is even more “Swiss” than Swiss law itself. For example, the new Code of Obligations implements the changes proposed by the Swiss scholars Pierre Widmer and Pierre Wessner (P. Widmer, P. Wessner, Révision et unification du droit de la responsabilité civile. Rapport explicatif, Berne 2000, https://www.bj.admin.ch/dam/bj/fr/data/wirtschaft/gesetzgebung/archiv/haftpflicht/vn-ber-f.pdf.download.pdf/vn-ber-f.pdf), although Switzerland ultimately rejected this draft reform of civil liability (more on this: E. Büyüksagis, Le nouveau droit turc des obligations, Bale 2014).

Of course, there are areas in which we can see changes that can be considered as inspired by social factors. In particular, we have recently seen reforms that allow imams to fulfil the role of civil servants in marriage ceremonies. However, the Turkish Civil Code and the Code of Obligations still stand as monuments dedicated to the modernisation efforts of Turkish society.

Posted by Michał Tutaj, PhD Candidate at the University of Warsaw; Associate at CMS Cameron McKenna Nabaro Olswang in Warsaw. Michał’s PhD thesis is titled ‘Transplantation of the Swiss Civil Law into Turkey‘.

This piece belongs to Season 2 of the “Cross-jurisdictional dialogues in the Interwar period” series dedicated to less-known legal transfers which have had a palpable impact on the advancement of the law. The Interwar period was a time of disillusionment with well-established paradigms and legislative models, but also a time of hope in which comparative dialogue and exchange of ideas between jurisdictions thrived. The series is edited by Prof Yseult Marique (Essex University) and Dr Radosveta Vassileva (Middlesex University). To access the other pieces from this series, either select the ‘Interwar Dialogue’ category or click on the #Series_Interwar_Dialogue tag on the BACL Blog.

Suggested citation: M Tutaj, ‘The Turkish Civil Code and Code of Obligations of 1926 and the Charm of Swiss Civil Law’, BACL Blog, available at https://british-association-comparative-law.org/2024/02/23/the-turkish-civil-code-and-code-of-obligations-of-1926-and-the-charm-of-swiss-civil-law-by-michal-tutaj/

1 Comment

Comments are closed.